| . |

The comic strip was born in the Sunday comic supplements of "yellow" or sensationalist newspapers like William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal and Joseph Pullitzer's New York World. It existed in part to help these papers sell their most valuable commodity: a window onto the city that could provide a sense of community. Comic illustrations could appeal to a wide variety of readers, including immigrants just beginning to learn English. Sports cartoons united city-dwellers around a common spectacle that could be shared by all, while cartoons of public figures created a similarly sharable spectacle out of the city's officials and celebrities. By classifying urbanites into types, some strips aimed to extend the reader's circle of specular acquaintance beyond celebrities to include the common man and woman. Characters in strips from the early 1900s rarely had proper names; rather than claiming the individuated but manifestly imaginary identity of a fictional character, early comic strip characters were frequently presented as generalized representations of the reality of human nature. Artist T. E. Powers favored this character-type approach to visual humor, specializing in strips with titles like "Do You Know This Man?" When an artist did grant a character a proper name, the name often identified the character as the distilled essence of some common character trait, as in the case of the 1905 strip "You Know Mr. Hoggit." The technique of naming a character according to a personality trait was perfected by Gus Mager, who exposed human foibles by representing them in the form of anthropomorphic monkeys with names like Henpecko, Braggo, Coldfeeto, and Tightwaddo. The authors of people-watching strips like these assumed the pose of the bemused observer of the city street's human parade. Of course community is built on exclusion as well as on common experience, and type-watching frequently meant racial, class and ethnic humor. Black-face savages like "Sahara Sam" (appearing on the pages of The World's 1897 Sunday comic supplements) abounded. A series of strips printed on the Home Page of the 1905 The New York Evening Journal, for example, depicts "The Eternal Feminine," a female character who represents all females. The Yellow Kid himself--the character identified by most histories of the comics as the origin of the comic strip form--embodied a similar strategy. R. F. Outcault's creation presented the reader with the distilled essence of the lovable street urchin and so helped to establish the tradition of class stereotypes in the comics. Whether we find their representations offensive or appealing, the Yellow Kid, type-watching strips in general, the sports strips, and news strips all aimed to give the reader the same sort of intimate contact with the city, walking the line between documentary representation and fiction. This project involved a claim to a certain kind of transparency: the comic strip sold a vantage point onto real scenes in the city, its class structure, and its economy. Indeed, at times the compositions of comic artists aimed to create the impression that the reader could step into the action in the pictures as a full participant . But while the strips tried to create an image that could act as a portal, the very act of marketing that image distanced the world beyond the portal from the reader's world. Images of public figures, human nature, sporting events, and stereotypes helped the newspapers sell a sense of community to their urban market, but none of these images could be owned exclusively. It is not surprising, then, that as comic strip artists and their employers confronted the role of their creations in the marketplace and the status of those creations as valuable items of intellectual property, they tended to see their cartoons less as doorways to the real and more as things or places in themselves. The newly discovered opacity of the comic strip as a salable world in its own right eventually brought some artists to reconsider the nature of their relationship to their product and their consumers.

But the absence of a copyright infringement suit did not mean the absence of a conflict in this case. As the bidding war over Outcault shows, the struggle of newspaper companies over ownership of comic strip worlds did not begin in a legal arena but in the marketplace. The rival versions of the Kid engaged in fierce campaigns for the attention of readers, campaigns that found their way into the cartoons themselves. As each artist tried to incorporate the highly publicized competition between the two Kids into the logic of the character and the strip, each strip's portrait of the Kid's slum neighborhood began to resolve into a representation of the reader's relation to the more ambiguous reality of the textual commodity itself. Simultaneously, the fictional worlds created by these artists grew gradually more remote from the urban community.

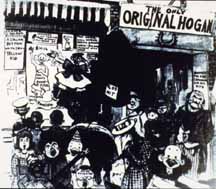

Luks takes a more direct approach in one of his cartoons on the subject. Rather than deny the existence of the rival cartoon, he presents us with a caricature of the mustachioed Outcault in the act of drawing his Kid. Standing in a store-front window on the margins of the drawing, Outcault comes across as a fraud as he hawks cheap, "copyrighted" sketches of the Yellow Kid as "souvenirs" (souvenirs, one presumes, of The World's "real" version of the strip). In the center of Luks' drawing a sign boldly proclaims, "The Only Original Hogan."

The informal resolution of potential intellectual property conflicts implemented by The Journal and The World in this case reinforced the impression given by Luks's cross-over strips that the setting of these strips was actually a kind of "corporate space" defined by the boundaries of the comic supplement rather than by any real geography. The paper that first published the strip owned the title of the feature--"Hogan's Alley." Although the characters could migrate, the newspaper owned the framing reality. When, after leaving The Journal, Outcault started drawing Buster Brown for The New York Herald, a similar defection by Outcault resulted in a similar resolution. This time, however, the resolution was enforced by the courts. Hearst lured Outcault back to The Journal, the artist took Buster Brown with him, and The Herald continued to produce its own version of the strip. Outcault sued The Herald to stop the rival strip, The Herald sued Hearst's Star Company, and the court decided that both papers could print cartoons starring Buster. Only The Herald, however, could publish them under the copyrighted title "Buster Brown." The separation of the characters and style of a strip from the title had become a standard, and cropped up in the careers of other artists as well. When, for example, Rudolph Dirks left Hearst's paper behind to sign up with The World, he also left behind the title "The Katzenjammer Kids" and took up the title "The Captain and the Kids." And, as in the case of the Yellow Kid, this move preceded a shift away from realistic settings toward more remote settings like ships and tropical islands.

As the disputes described above suggest, ownership of characters was an issue distinct from the ownership of titles and fictive universes. If the commodification of comic strip worlds tended to foster their transformation from realistic settings into corporate alternate realities, then the commodification of individual characters fostered its own, distinct transformations. Again, the history of the Yellow Kid gives us important clues as to the nature of those transformations. Although Outcault had little success in preventing The Herald from using Buster Brown, and doesn't seem to have tried to prevent The Journal from producing its own Yellow Kid cartoons, Winchester notes that Outcault assiduously and effectively litigated to prevent unauthorized uses of the characters from cutting into his own lucrative product-licensing business (22). As Ian Gordon has amply illustrated, both Buster Brown and the Yellow Kid proved to be gold mines when it came to selling the rights for toys and other products bearing the likenesses of the characters, and Outcault vigorously defended his cash cow. This cottage product-licensing industry of Outcault's seems to have brought about a revolution in the way he thought of his character. Other descriptions of the Kid by Outcault represent him as a collective portrait of real street kids. The following passage, however, portrays the Kid as a sort of commodified Pinnochio--a clearly fictional character who uses his value as a marketing gimmick to will himself into reality. Sheer repetition of the Kid's image brings him to life:

This narration highlights two crucial points about the development of the Kid's character. First, it shows that that Outcault now thinks of the Kid as an individualized, distinctive person rather than as a type. Second, it suggests that this shift is wrapped up in the discovery of new ways to market the image of this sort of distinctive character. Thus the insistence of the market's demand for reproductions of the Kid's image becomes in Outcault's account the insistence of a fictional character for a life of its own. In the process of explaining why it was in the interest of eighteenth-century authors to cultivate the fictionality of their narratives, Catharine Gallagher notes that an author can defend her ownership of a fiction more easily than her ownership of a narrative based on historical events or a common story (158-162). In the history of English copyright litigation following the Statute of Anne, the originality of a work became a crucial legal test of its status as the exclusive property of its author, and a work of fiction is arguably the most "original" of literary commodities since it is not simply a "copy" of reality. A fictional character conceived as a unique individual is thus more ownable than a character conceived as a type. It is not surprising, then, that we see the sort of transformation illustrated above by the Kid being enacted in other early strips as well. Gus Mager's monkeys, originally named for generalized personality traits ("Coldfeeto the Monk," etc.), eventually metamorphose into the regular strip "Sherlocko the Monk." Sherlocko is a detective rather than a character flaw, and in spite of the title he no longer even seems to be a monkey . The copyrighting of strips themselves did not seem to make individual characters valuable enough to bring about this transformation. A copyrighted cartoon was conceived as a single work, and the ownability of its individual elements could not be derived from the ownability of the whole. Only reproduction in ancillary products could give comic strip characters a legal life that transcended any particular physical form. When the 1924 case King Features Syndicate v. Fleischer determined that an unauthorized toy version of Barney Google's Horse "Spark-Plug" constituted a copyright infringement, the court gave full protection to the sort of product licensing Outcault had represented in fantastic terms as the expression of a fictional character's will to exist. Product-licensing convinced courts to consider comic strip characters as intellectual property. In so doing it blazed the trail for later applications of trademark doctrine to characters in serial fictions. Trademark protection, in stark contrast to copyright protection, can be renewed indefinitely. This potential permanence stems from trademark law's original function as a way of assuring that consumers could always know the origin of a given product through the presence of the originating company's distinctive mark. A trademark is a way of making a brand name a form of property, primarily so that consumers know what they are getting when they buy a particular brand but also so that companies can use the brand as a receptacle to accumulate the value generated by consumer loyalty (i.e., "brand equity"). The latter function makes trademark a natural tool for preserving the value generated by a cultural product's loyal audience. It is not surprising, then, that in the second half of the twentieth century the trademark has increasingly been used to protect intellectual properties that don't fit easily within the boundaries of the copyrightable "work." In the 1954 case of Warner brothers Pictures, Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting Co., the court ruled that Dashiell Hammett had the right to use the character Sam Spade in sequels to The Maltese Falcon in spite of the fact that Hammett had already sold the motion picture rights of the original Sam Spade novel to Warner. Jane Gaines, in her book Contested Culture, points out that this case proved the unreliability of copyright law for protecting the integrity of the cultural commodity from reproduction (211-223). The court reasoned that copyright could only protect the literary work as a unified whole, not individual elements of the work such as characters. An ongoing series, however, never achieves the completion that would limit the boundaries of the ownable work. Through the consistent association of its name with the distinctive symbols, pictures, or words representing the characters and settings in its serial fictions, a company can establish a relationship with these fictive elements that transcends any particular story in which they may appear. The characters and settings in the series become trademarks, or signs which represent the company itself, and can thus be owned for an indefinite period of time. Gaines uses the example of Superman comic book, movie, and television serials to show that the serial form can preserve the character as property by making the character into a trademark rather than a merely copyrightable fiction. The reproduction of Superman's image on various tie-in products further consolidates the character's protection as property under U.S. trademark law. In the U.S., the consistent association of a particular image with a particular company strengthens that company's right to register the image as a trademark and claim trademark protection. Thus, in Gaines's words, "to industrially produce an aluminum cake pan in the shape of Superman is to reassert (by a kind of high-finance squatter's rights) ownership and economic control over the most commonplace signs of culture in everyday circulation" (223). Trademarked narrative elements thrive on reproduction, for the more often they are reproduced, and the more different forms in which they are reproduced, the more likely the courts are to associate them with the companies that generate them and to acknowledge their status as trademarks. In short, the commercial life of a character depends on its reproduction. This makes the comic strip character a peculiar sort of resource: one which cannot be used up, one which in fact becomes more valuable through profligate "spending." As the culture industry grew, this seemingly fantastic form of commodity became a fact of everyday life and thus a subject worth imaginative attention for the successful comic strip artist. Confronted with the momentum of value built through the Kid's reproduction, Outcault imagined it as the growing insistence of a fictional character's will to exist. Other artists imagined the economy of reproduction in different terms, but it continued to be an insistent object of their attention as the comic strip developed as a form.

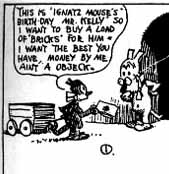

Bricks are the only things bought and sold in Coconino, so that, on one level, their abstract and omnipresent box-like shape comes to stand in for all commodities through an absurd reduction that is in itself fabulistic. But more than this, Herriman's bricks are fantastic precisely because they depart from the logic of commodities in general. Rarely do we see bricks being produced, for example. The recycling scenario we saw above is much closer to the norm. Bricks are not used up in the act of consumption, and then replaced with new ones; rather, the same bricks circulate endlessly through Ignatz and Krazy's bizarre economy of desire.

The form of the comic strip was, then, shaped by the efforts of comic artists to construct a vision of the reproductive economy in which they participated. Early comic artists conceived of their labor as a way to deliver the real city to their audience, but intellectual property conflicts and the deeply commodified nature of their art eventually led many artists to see their products as inhabiting an order of reality entirely separate from any urban setting, a reality whose boundaries were coextensive with the boundaries of the media corporation. Similarly, the enhanced ownability of fictional characters encouraged artists to shy away from "real" characters and generalized types. The form of the comic strip matured in tandem with the legal and business practices that addressed the special problems and ambiguities of an industry based on reproduction. |

|||||||||||||||||||