Josiah G. Holland.

IN WHICH A HEAVENLY WITNESS APPEARS WHO CANNOT BE CROSS EXAMINED, AND BEFORE WHICH THE DEFENSE UTTERLY BREAKS DOWN.

Mr. Belcher had grown old during the hour. His consciousness of guilt, his fear of exposure, the threatened loss of his fortune, and the apprehension of a retribution of disgrace were sapping his vital forces, minute by minute. All the instruments that he had tried to use for his own base purposes were turned against himself The great world that had glittered around the successful man was growing dark, and, what was worse, there were none to pity him. He had lived for himself; and now, in his hour of trouble, no one was true to him, no one loved him—not even his wife and children!

He gave a helpless, hopeless sigh, as Mr. Balfour called to the witness stand Prof. Albert Timms.

Prof. Timms was the man already described among the three new witnesses, as the one who seemed to be conscious of bearing the world upon his shoulders, and to find it so inconsiderable a burden. He advanced to the stand with the air of one who had no stake in the contest. His impartiality came from indifference. He had an opportunity to show his knowledge and his skill, and he delighted in it. [*401]

"What is your name, witness?" inquired Mr. Balfour.

"Albert Timms, at your service."

"I have at present the charge of a department in the School of Mines. My specialties are chemistry and microscopy."

"You are specially acquainted with these branches of natural science, then."

"Have you been regarded as an expert in the detection of forgery?"

"I have been called as such in many cases of the kind, sir."

"Then you have had a good deal of experience in such things, and in the various tests by which such matters are determined?"

"Have you examined the assignment and the autograph letters which have been in your hands during the recess of the Court?"

"Do you know either the plaintiff or the defendant in this case?"

"I do not, sir. I never saw either of them until to-day."

"Has any one told you about the nature of these papers, so as to prejudice your mind in regard to any of them?"

"No, sir. I have not exchanged a word with any one in regard to them.''

"What is your opinion of the two letters?"

"That they are veritable autographs."

"From the harmony of the signatures with the text of the body of the letters, by the free and natural shaping and interflowing of the lines, and by a general impression of truthfulness which it is very difficult to communicate in words."

"What do you think of the signatures to the assignment?"

"I think they are all counterfeits but one." [*402]

"Prof. Timms, this is a serious matter. You should be very sure of the truth of a statement like this. You say you think they are counterfeits: why?"

"If the papers can be handed to me," said the witness, `'I will show what leads me to think so."

The papers were handed to him, and, placing the letters on the bar on which he had been leaning, he drew from his pocket a little rule, and laid it lengthwise along the signature of Nicholas Johnson. Having recorded the measurement, he next took the corresponding name on the assignment.

"I find the name of Nicholas Johnson of exactly the same length on the assignment that it occupies on the letter," said he.

"Is that a suspicious circumstance?"

"It is, and, moreover,"(going on with his measurements) "there is not the slightest variation between the two signatures in tile length of a letter. Indeed, to the naked eye, one signature is the counterpart of the other, in every characteristic."

"How do you determine, then, that it is anything but a genuine signature?"

"The imitation is too nearly perfect."

"Well; no man writes his signature twice alike. There is not one chance in a million that he will do so, without definitely attempting to do so, and then he will be obliged to use certain appliances to guide him."

"Now will you apply the same test to the other signature?"

Prof. Timms went carefully to work again with his measure He examined the form of every letter in detail, and compared it with its twin, and declared, at the close of his examination, that he found the second name as close a counterfeit as the first.

"Both names on the assignment, then, are exact fac-simile of the names on the autograph letters," said Mr. Balfour

"They are, indeed, sir—quite wonderful reproductions." [*403]

"The work must have been done, then, by a very skillful man," said Mr. Balfour.

The professor shook his head pityingly. "Oh, no, sir," he said. "None but bunglers ever undertake a job like this. Here, sir, are two forged signatures. If one genuine signature, standing alone, has one chance in a million of being exactly like any previous signature of the writer, two standing together have not one chance in ten millions of being exact fac-similes of two others brought together by chance.

"How were these fac-similes produced?" inquired Mr. Balfour.

"They could only have been produced by tracing first with a pencil, directly over the signature to be counterfeited."

"Well, this seems very reasonable, but have you any further tests?"

"Under this magnifying glass," said the professor, pushing along his examination at the same time, "I see a marked difference between the signatures on the two papers, which is not apparent to the naked eye. The letters of the genuine autograph have smooth, unhesitating lines; those of the counterfeits present certain minute irregularities that are inseparable from pains-taking and slow execution. Unless the Court and the jury are accustomed to the use of a glass, and to examinations of this particular character, they will hardly be able to see just what I describe, but I have an experiment which will convince them that I am right."

"Can you perform this experiment here, and now?"

"I can, sir, provided the Court will permit me to establish the necessary conditions. I must darken the room, and as I notice that the windows are all furnished with shutters, the matter may be very quickly and easily accomplished."

"Will you describe the nature of your experiment?"

"Well, sir, during the recess of the Court, I have had photographed upon glass all the signatures. These, with the aid of a solar microscope, I can project upon the wall behind the jury, immensely enlarged, so that the peculiarities I have [*404] described may be detected by every eye in the house, with others, probably, if the sun remains bright and strong, that I have not alluded to."

"The experiment will be permitted," said the judge, "and the officers and the janitor will give the Professor all the assistance he needs."

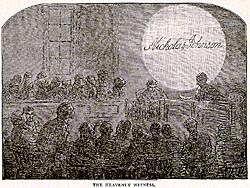

Gradually, as the shutters were closed, the room grew dark, and the faces of Judge, Jury and the anxious-looking parties within the bar grew weird and wan among the shadows. A strange silence and awe descended upon the crowd. The great sun in heaven was summoned as a witness, and the sun would not lie. A voice was to speak to them from a hundred millions of miles away—a hundred millions of miles near the realm toward which men looked when they dreamed of the Great White Throne.

They felt as a man might feel, were he conscious, in the darkness of the tomb, when waiting for the trump of the resurrection and the breaking of the everlasting day. Men heard their own hearts beat, like the tramp of trooping hosts; yet there was one man who was glad of the darkness. To him the judgment day had come; and the closing shutters were the rocks that covered him. He could see and not be seen. He could behold his own shame and not be conscious that five hundred eyes were upon him.

All attention was turned to the single pair of shutters not entirely closed. Outside of these, the professor had established his heliostat, and then gradually, by the aid of drapery, he narrowed down the entrance of light to a little aperture where a single silver bar entered and pierced the darkness like a spear. Then this was closed by the insertion of his microscope, and, leaving his apparatus in the hands of an assistant, he felt his way back to his old position.

"May it please the Court, I am ready for the experiment," he said.

"The witness will proceed," said the judge.

"There will soon appear upon the wall, above the heads of [*405] the Jury," said Prof. Timms, "the genuine signature of Nicholas Johnson, as it has been photographed from the autograph letter. I wish the Judge and Jury to notice two things in this signature—the cleanly-cut edges of the letters, and the two lines of indentation produced by the two prongs of the pen, in its down-stroke. They will also notice that, in the up-stroke of the pen, there is no evidence of indentation whatever. At the point where the up-stroke begins, and the down-stroke ends, the lines of indentation will come together and cease."

As he spoke the last word, the name swept through the darkness over an unseen track, and appeared upon the wall, within a halo of amber light. All eyes saw it, and all found the characteristics that had been predicted. The professor said not a word. There was not a whisper in the room. When a long minute had passed, the light was shut off.

"Now," said the professor, "I will show you in the same place, the name of Nicholas Johnson, as it has been photographed from the signatures to the assignment. What I wish you to notice particularly in this signature is, first, the rough and irregular edges of the lines which constitute the letters. They will be so much magnified as to present very much the appearance of a Virginia fence. Second, another peculiarity which ought to be shown in the experiment-one which has a decided bearing upon the character of the signature. If the light continues strong, you will be able to detect it. The lines of indentation made by the two prongs of the pen will be evident, as in the real signature. I shall be disappointed if there do not also appear a third line, formed by the pencil which originally traced the letters, and this line will not only accompany, in an irregular way, crossing from side to side, the two indentations of the down-strokes of the pen, but it will accompany irregularly the hair-lines. I speak of this latter peculiarity with some doubt, as the instrument I use is not the best which science now has at its command for this purpose, though competent under perfect conditions." [*406]

He paused, and then the forged signatures appeared upon the wall. There was a universal burst of admiration, and then all grew still—as if those who had given way to their feelings were suddenly stricken with the consciousness that they were witnessing a drama in which divine forces were playing a part. There were the ragged, jagged edges of the letters; there was the supplementary line, traceable in every part of them. There was man's lie—revealed, defined, convicted by God's truth!

The letters lingered, and the room seemed almost sensibly to sink in the awful silence. Then the stillness was broken by a deep voice. What lips it came from, no one knew, for all the borders of the room were as dark as night. It seemed, as it echoed from side to side, to come from every part of the house: "Mene mene, tekel upharsin!" Such was the effect of these words upon the eager and excited, yet thoroughly solemnized crowd, that when the shutters were thrown open, they would hardly have been surprised to see the bar covered with golden goblets and bowls of wassail, surrounded by lordly revellers and half-nude women, with the stricken Belshazzar at the head of the feast. Certainly Belshazzar, on his night of doom, could hardly have presented a more pitiful front than Robert Belcher, as all eyes were turned upon him. His face was haggard, his chin had dropped upon his breast, and he reclined in his chair like one on whom the plague had laid its withering hand.

There stood Prof. Timms in his triumph. His experiment had proved to be a brilliant success, and that was all he cared for.

"You have not shown us the other signatures, "said Mr. Balfour.

"False in one thing, false in all," responded the professor, shrugging his shoulders. "I can show you the others; they would be like this; you would throw away your time."

Mr. Cavendish did not look at the witness, but pretended to write. [*407]

"Does the counsel for the defense wish to question the witness?" inquired Mr. Balfour, turning to him.

"You can step down," said Mr. Balfour. As the witness passed him, he quietly grasped his hand and thanked him. A poorly suppressed cheer ran around the court-room as he resumed his seat. Jim Fenton, who had never before witnessed an experiment like that which, in the professor's hands, had been so successful, was anxious to make some personal demonstration of his admiration. Restrained from this by his surroundings, he leaned over and whispered: "Perfessor, you've did a big thing, but it's the fust time I ever knowed any good to come from peekin' through a key-hole."

"Thank you," and the professor nodded sidewise, evidently desirous of shutting Jim off, but the latter wanted further conversation.

"Was it you that said it was mean to tickle yer parson?" inquired Jim.

"What?" said the astonished professor, looking round in spite of himself.

"Didn't you say it was mean to tickle yer parson? It sounded more like a furriner," said Jim.

When the professor realized the meaning that had been attached by Jim to the "original Hebrew," he was taken with what seemed to be a nasal hemorrhage that called for his immediate retirement from the court-room.

What was to be done next? All eyes were turned upon the counsel who were in earnest conversation. Too evidently the defense had broken down utterly. Mr. Cavendish was angry, and Mr. Belcher sat beside him like a man who expected every moment to be smitten in the face, and who would not be able to resent the blow.

"May it please the Court," said Mr. Cavendish, "it is impossible, of course, for counsel to know what impression this testimony has made upon the Court and the jury. Dr. Barhydt, after a lapse of years, and dealings with thousands [*408] of patients, comes here and testifies to an occurrence which my client's testimony makes impossible; a sneak discovers a letter which may have been written on the third or the fifth of May, 1860—it is very easy to make a mistake in the figure, and this stolen letter, never legitimately delivered,—possibly never intended to be delivered under any circumstances—is produced here in evidence; and, to crown all, we have had the spectacular drama in a single act by a man who has appealed to the imaginations of us all, and who, by his skill in the management of an experiment with which none of us are familiar, has found it easy to make a falsehood appear like the truth. The counsel for the plaintiff has been pleased to consider the establishment or the breaking down of the assignment as the practical question at issue. I cannot so regard it. The question is, whether my client is to be deprived of the fruits of long years of enterprise, economy and industry; for it is to be remembered that, by the plaintiff's own showing, the defendant was a rich man when he first knew him. I deny the profits from the use of the plaintiff's patented inventions, and call upon him to prove them. I not only call upon him to prove them, but I defy him to prove them. It will take something more than superannuated doctors, stolen letters and the performances of a mountebank to do this."

This speech, delivered with a sort of frenzied bravado, had a wonderful effect upon Mr. Belcher. He straightened in his chair, and assumed his old air of self-assurance. He could sympathize in any game of "bluff," and when it came down to a square fight for money his old self came back to him. During the little speech of Mr. Cavendish, Mr. Balfour was writing, and when the former sat down, the latter rose, and, addressing the Court, said: "I hold in my hand a written notice, calling upon the defendant's counsel to produce in Court a little book in the possession of his client entitled 'Records of profits and investments of profits from manufactures under the Benedict patents,' and I hereby serve it upon him." [*409]

Thus saying, he handed the letter to Mr. Cavendish, who received and read it.

Mr. Cavendish consulted his client, and then rose and said: "May it please the Court, there is no such book in existence."

"I happen to know, "rejoined Mr. Balfour, "that there is such a book in existence, unless it has recently been destroyed. This I stand ready to prove by the testimony of Helen Dillingham, the sister of the plaintiff."

"The witness can be called," said the judge.

Mrs. Dillingham looked paler than on the day before, as she voluntarily lifted her veil, and advanced to the stand. She had dreaded the revelation of her own treachery toward the treacherous proprietor, but she had sat and heard him perjure himself, until her own act, which had been performed on behalf of justice, became one of which she could hardly be ashamed.

"Mrs. Dillingham," said Mr. Balfour, "have you been on friendly terms with the defendant in this case?"

"I have, sir," she answered. "He has been a frequent visitor at my house, and I have visited his family at his own."

"Was he aware that the plaintiff was your brother?"

"Has he, from the first, made a confidant of you?"

"Do you know Harry Benedict—the plaintiff's son?"

"How long have you known him?"

"I made his acquaintance soon after he came to reside with you, sir, in the city."

"Did you seek his acquaintance?"

"Mr. Belcher wished me to do it, in order to ascertain of him whether his father were living or dead."

"You did not then know that the lad was your nephew?" [*410]

"Have you ever told Mr. Belcher that your brother was alive?"

"I told him that Paul Benedict was alive, at the last interview but one that I ever had with him."

"Did he give you at this interview any reason for his great anxiety to ascertain the facts as to Mr. Benedict's life or death?"

"Was there any special occasion for the visit you allude to?"

"I think there was, sir. He had just lost heavily in International Mail, and evidently came in to talk about business. At any rate, he did talk about it, as he had never done before."

"Can you give us the drift or substance of his conversation and statements?"

"Well, sir, he assured me that he had not been shaken by his losses, said that he kept his manufacturing business entirely separate from his speculations, gave me a history of the manner in which my brother's inventions had come into his hands, and, finally, showed me a little account book, in which he had recorded his profits from manufactures under what he called the Benedict Patents."

"Did you read this book, Mrs. Dillingham?"

"Did you hear me serve a notice on the defendant's counsel to produce this book in Court?"

"In that notice did I give the title of the book correctly?"

"Was this book left in your hands for a considerable length of time?"

"It was. sir. for several hours." [*411]

"I did, sir, every word of it."

"Are you sure that you made a correct copy?"

"I verified it, sir, item by item, again and again."

"Can you give me any proof corroborative of your state. ment that this book has been in your hands?"

"A letter from Mr. Belcher, asking me to deliver the book to his man Phipps."

"Is that the letter?" inquired Mr. Balfour, passing the note into her hands.

"May it please the Court," said Mr. Balfour, turning to the Judge, "the copy of this account-book is in my possession, and if the defendant persists in refusing to produce the original, I shall ask the privilege of placing it in evidence."

During the examination of this witness, the defendant and his counsel sat like men overwhelmed. Mr. Cavendish was angry with his client, who did not even hear the curses which were whispered in his ear. The latter had lost not only his money, but the woman whom he loved. The perspiration stood in glistening beads upon his forehead. Once he put his head down upon the table before him, while his frame was convulsed with an uncontrollable passion. He held it there until Mr. Cavendish touched him, when he rose and staggered to a pitcher of iced water upon the bar, and drank a long draught. The exhibition of his pain was too terrible to excite in the beholders any emotion lighter than pity.

The Judge looked at Mr. Cavendish who was talking angrily with his client. After waiting for a minute or two, he said: "Unless the original of this book be produced, the Court will be obliged to admit the copy. It was made by one who had it in custody from the owner's hands."

"I was not aware," said Mr. Cavendish fiercely, "that a crushing conspiracy like this against my client could be car- [*412] ried on in any court of the United States, under judicial sanction."

"The counsel must permit the Court," said the Judge calmly, "to remind him that it is so far generous toward his disappointment and discourtesy as to refrain from punishing him for contempt, and to warn him against any repetition of his offense."

Mr. Cavendish sneered in the face of the Judge, but held his tongue, while Mr. Balfour presented and read the contents of the document. All of Mr. Belcher's property at Sevenoaks, his rifle manufactory, the goods in Talbot's hands, and sundry stocks and bonds came into the enumeration, with the enormous foreign deposit, which constituted the General's "anchor to windward." It was a handsome showing. Judge, jury and spectators were startled by it, and were helped to understand, better than they had previously done, the magnitude of the stake for which the defendant had played his desperate game, and the stupendous power of the temptation before which he had been led to sacrifice both his honor and his safety.

Mr. Cavendish went over to Mr. Balfour, and they held a long conversation, sotto voce. Then Mrs. Dillingham was informed that she could step down, as she would not be wanted for cross-examination. Mr. Belcher had so persistently lied to his counsel, and his case had become so utterly hopeless, that even Cavendish practically gave it up.

Mr. Balfour then addressed the Court, and said that it had been agreed between himself and Mr. Cavendish, in order to save the time of the Court, that the case should be given to the jury by the Judge, without presentation or argument of counsel.

The Judge occupied a few minutes in recounting the evidence, and presenting the issue, and without leaving their seats the jury rendered a verdict for the whole amount of damages claimed.

The bold, vain-glorious proprietor was a ruined man. The [*413] consciousness of power had vanished. The law had grappled with him, shaken him once, and dropped him. He had had a hint from his counsel of Mr. Balfour's intentions, and knew that the same antagonist would wait but a moment to pounce upon him again, and shake the life out of him. It was curious to see how, not only in his own consciousness, but in his appearance, he degenerated into a very vulgar sort of scoundrel. In leaving the Court-room, he skulked by the happy group that surrounded the inventor, not even daring to lift his eyes to Mrs. Dillingham. When he was rich and powerful, with such a place in society as riches and power commanded, he felt himself to be he equal of any woman; but he had been degraded and despoiled in the presence of his idol, and knew that he was measurelessly and hopelessly removed from her. He was glad to get away from the witnesses of his disgrace, and the moment he passed the door, he ran rapidly down the stairs, and emerged upon the street.