Some Curiosities of Modern Photography. Part II.

By William G. FitzGerald.

As will be occasionally seen in this article, certain experts devote themselves to particular branches of photography. The name of Captain Hayes is associated with equine photography, and he himself has travelled all over India, China, and South Africa, armed with a hand-camera. As the result of an argument with Mr. John Charlton, the chief artist of the Graphic, Captain Hayes once produced a photograph of a horse with all four legs on the ground, yet showing a decided sense of movement.

All sorts of odd means are devised to make horses that are going to be photographed look smart. The official photographer at the Royal Military Repository tells me he has a shrill whistle blown at the critical moment; or the sergeant-major who assists him opens an umbrella sharply, causing the horse to prick up its ears.

|

Another famous animal photographer, Mr. Frederick Haes, found that the best way to get a good photo. of a rhinoceros was to direct the animal's attention to a boy clad in a bright blue coat. "Wild animals," adds Mr. Haes, "have a strange objection to a man in his shirt-sleeves."

Certainly one of the most interesting marvels of photography is that the mysterious eye of the camera sees objects which are absolutely invisible to the human eye, the telescope, or the microscope.

An expert can take a sheet of paper prepared with gelatine and bichromate of potash, and can photograph on it a secret letter, containing, it may be, treasonable matter. This done, he may sit down and write a garrulous letter about the crops, the weather, and the baby's health. The recipient, of course, cares for none of these things, but wets the sheet with plain water, holds it up to the light, and literally reads between the lines. When dry, the document defies detection, and it can be moistened and dried again as often as the recipient pleases.

Mr. Traill Taylor tells me that a room which appears visually quite dark may be full of the ultra-violet rays of the spectrum, and, paradoxical as it may seem, photographs may be taken in that dark light. Dr. Gladstone, F.R.S., has traced invisible drawings on white cardboard, the "ink " used being such fluorescents as mineral uranite and disulphate of quinine. When photographed, the drawings have come out bold and clear.

Mr. Taylor relates a funny story concerning a young lady of scientific, and at the same time mischievous, proclivities.

This young lady painted upon her fair brow with fluorescent liquid a death's head and cross-bones, and she then demurely visited a photographer's to have her portrait instantaneously taken. All went well until the operator had developed the plate, and then it became evident that he was having a row with his assistant, whom he blamed for coating a dirty plate. After apologies, a second negative was taken, and then the operator fetched his master from downstairs. A third attempt was made, when sounds of a heated altercation were heard, followed by a scuffle.

|

Without expressing an opinion of my own, I should like to touch upon the so-called psychic or ghost photography, conducted in the presence of a spiritualistic medium. When one learns, by the way, that Professor Crookes, F.R.S., and Dr. Alfred Russel Wallace have investigated the subject, believe in it, and possess collections of spirit photos., one is almost tempted to think that there must be "something in it."

|

The best-known experiment in ghost photography was conducted by Mr. Traill Taylor in the presence of the well-known medium, Mr. David Duguid—a truly reassuring name, at any rate. Mr. Taylor not only used his own unopened packages of dry plates and conducted the developing himself, but he set a watch upon his own camera in the guise of a duplicate one of the same focus. And yet ghosts appeared—spirits of departed friends, all nicely draped (Fig. 22).

|

But, perhaps, when I turn to stellar photography the average reader will be able to form a more adequate conception of the marvels of modern photography.

As well as peering into the depths of the earth and the sea, and making visible the invisible, the omniscient eye of the camera defeats the telescope on its own ground, or, rather, in its own element. In an area which did not contain one visible star, ten thousand have been found by photography. We have photos. of lunar mountains, and egg-shaped masses of hazy nebulae which the human eye, aided by the most powerful telescope in existence, could never have discovered (Fig. 23).

Here is the weapon of the New Astronomy. A gigantic telescope, fitted as a camera, and carrying a plate of great sensitiveness, is exposed in the ordinary way, as a telescope only would be. The apparatus is driven by a huge clock, which causes the telescope to follow the stars for fifteen or twenty minutes, during which time a vast number of otherwise invisible astral bodies impress themselves on the plate. The eye of the camera, be it noted, does not tire; the longer it gazes, the more its sensitive vision takes in. The very composition of the stellar worlds has been determined by modern photography.

The man who has tackled the photography of animal locomotion in the most extraordinary, and at the same time most thorough, manner is unquestionably Professor Muybridge, of Pennsylvania University. It is interesting to learn how this scientist came to adopt the business of his life.

In 1872, Muybridge was official photographer to the United States Government on the Pacific Coast, and while at San Francisco, a dispute arose between two wealthy residents as to whether a fast-trotting horse had at any moment his four feet off the ground.

After experimenting for a few days, taking as a model the celebrated trotting horse, "Occident," who trotted a mile in two minutes and sixteen seconds, about a dozen negatives were obtained, which plainly showed that for some portion of his stride, at least, the horse was entirely free from contact with the ground. Indeed, seeing that some trotting-horses take a twenty-foot stride, it is difficult to understand why the dispute ever arose.

|

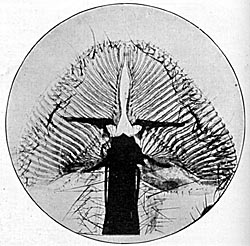

The apparatus now used by Professor Muybridge consists of an electrically controlled battery of twelve cameras, so arranged that a regulated succession of exposures can be made in any given time. When completed, his pictures are combined in an instrument of his own invention called the zoöpraxiscope, and projected on to a screen by an optical lantern, the result being that one finds it hard to believe one is not actually looking at the moving original.

When the professor lectured at the Royal Institution, there were among his audience the Prince and Princess of Wales and their daughters, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg, Sir Frederick Leighton, Professors Huxley, Gladstone, and Tyndall, and the late Lord Tennyson. On the screen before this imposing assembly horses walked, ambled, and leaped over hurdles in a perfectly natural manner; athletes and kangaroos jumped; birds flew; monkeys climbed trees; and ladies danced and carried on a fan flirtation. Yet the majority of the photographs, seen singly, seemed to depict ungraceful and impossible attitudes. Fig. 24 shows a really extra-ordinary series of Muybridge's photographs. The famous mare "Sallie Gardner," belonging to the well-known American sportsman, Leland Stanford, is shown running at a high rate of speed over the Palo Alto track. The negatives of these photographs were made at intervals of 27in. of distance, and about the 25th part of a second. They illustrate consecutive positions assumed in each 27in. of progress during a single stride of the mare. The vertical lines shown in the photograph were 27in. apart; and the exposure of each negative was rather less than the 2,000th part of a second.