Some Curiosities of Modern Photography. Part I.

By William G. FitzGerald

|

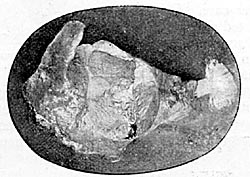

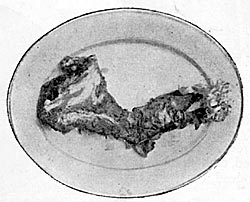

The secret of the daring and successful forgeries on Glyn's Bank was, as we all know, revealed by photography. The draft was made out for £48, but words, figures, and even perforations were punched clean out of the paper, and new pulp made and inserted. The human eye was absolutely unable to detect that the draft had been tampered with, yet a photograph showed the faint lines of the new pulp quite plainly. The forged draft was for £4,800.

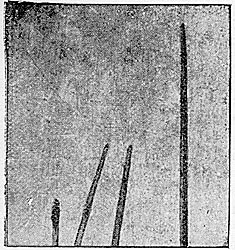

Putty used by burglars in removing panes of glass; sections of banisters; drinking glasses and newspapers have been photographically treated, the finger impressions being carefully compared with those of suspects in every case. I am bound to say, however, that in this country we are slow to introduce the marvels of modern science into our warfare against the expert criminal. We have no eminent chemist like Dr. Jeserich, of Berlin, who has for more than thirteen years been engaged in continuous conflict with the enemies of society. Like his learned predecessor and teacher, Professor Sonnenschein, Dr. Jeserich takes rank among the greatest photographic detectives of the civilized world; and I propose to give as briefly as possible a few of the curious cases that have come under his notice. Dr. Jeserich resorted to photography, or photo-micrography, in order to have the whiphand of other experts who disputed his microscopical observations. Eleven years ago a peculiarly atrocious murder was committed in Westphalia, and a small white hair was forwarded to Dr. Jeserich for examination. This hair was found upon the body of the victim—a girl—and was held to be of great importance, seeing that the accused murderer was a grey haired and bearded man. A hair from the beard of the latter was also forwarded for comparison.

The photo-micrographs certainly showed that the hairs were in some respects alike. Both had the same pith in the centre; both had the same air-channels, scales, and hollow spaces, and a certain fine structure of surface was common to both hairs under examination. For all that, the expert, looking at his photos., pronounced the hair found on the body to be that of an animal, solely because the pith extended to nearly the whole width of the shaft.

But what animal? Further experiments showed that the hair had been plucked from a dog: in every case photo-micrographs were compared; and, this fact ascertained, the case grew with amazing swiftness in the expert's hands.

|

The man under arrest for this murder was liberated on Dr. Jeserich's evidence. Barely a year later suspicion fell upon another person, who possessed a dog exactly coinciding with the above description. More scientific investigations followed, and about two months after his arrest the man confessed that he had murdered the girl.

|

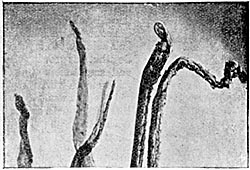

A photograph of the point of a hair found on one of the accused demonstrated scientifically that it had been taken from the victim's head. Indeed, not only was the point identical, but the shaft and root also coincided. Fig. 5 shows the well-defined, club-like root of this hair—a little thing, indeed, on which to decide life or death.

|  |