For the first half of this term, we studied the various projects that have been built at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (changed in 2011 from CHNM). As our focus shifts to the tools now being designed and offered by the center, it is a good time to reflect on the history of the RRCHNM projects. Typically, digital projects at the center fall into two categories: history/teaching sites and collection sites. In this post, I’m going to discuss the former.

The first online digital history project built at the center was Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, which offered a unique combination of primary sources, an overarching historical narrative, and limited numbers of image, audio, and video files. Each page on the site was written in HTML line-by-line, allowing very little flexibility. In general, pages include a linear narrative in text form, and sometimes have links along the left side for primary sources or images. Most links open in new windows, presumably to avoid interrupting the integrity of the main narrative. The design of the site was limited not only by the technical possibilities of the late 90s, but also because its purpose was limited to providing a history of the revolution. In a way this site functions as a text book, and so its design mimics book layout and interaction.

Although the site continues to function, the tools used to build it constrained the design, and even today, prevent center staff from easily translating its content to a new site.

The center has built only a few sites that offer specific histories; in the early 2000s, designs shifted toward more general history teaching, such as History Matters, a site that offers some historical information and narrative, but also encourages students to think like historians. In a way, History Matters tries to cover all the bases for teaching skills and content. Although it shares very nearly the timeline of the French Revolution site, History Matters was built to encompass a much broader range of content, and has a much larger scope of purpose. My colleague, Ben Hurwitz, has previously discussed the evolution of educational sites, so I will stick to technical developments.

Technically, History Matters is more complex than the Revolution site, but it shares the basic structure. The database was built by hand and the pages were coded in HTML. As a result, there are difficulties that arise when searching or cross-referencing pages. The layout strays further from book format, but was designed for smaller screens, which makes the whole site seem rather tiny on modern screens. Static pages and navigation by links show the age of the site, and like the first site, prevent easy translation to a new format.

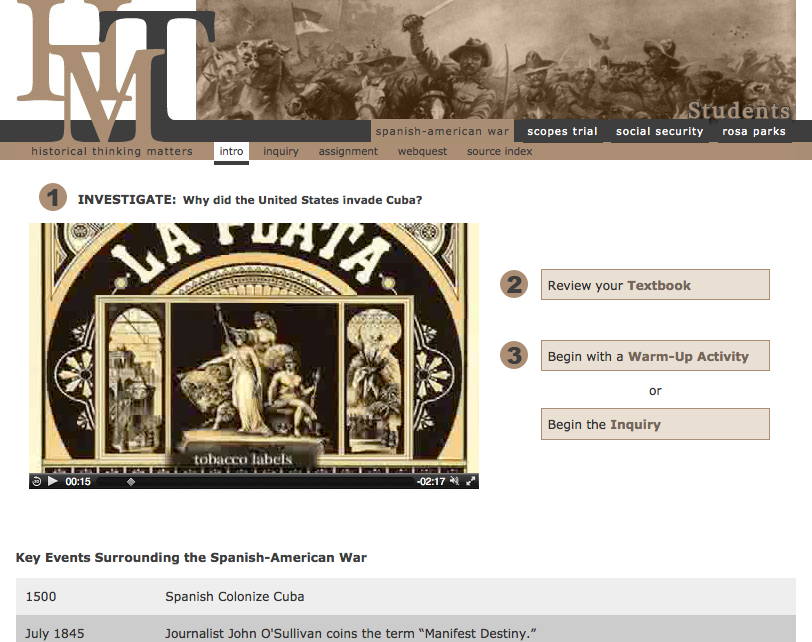

As Ben mentions, the next round of educational sites moved even further from strictly history to historical thinking and teaching content. The Historical Thinking Matters site, for instance, allows teachers to guide their students through a process of inquiry and investigation. The site uses more recent technical capability, such as embedded video, images that can be manipulated, javascript, and css style sheets. Pages are no longer static and coded in HTML, but are dynamic and draw from different sources. Unfortunately, despite the site’s success, it uses some tools that are now becoming obsolete. One of the major themes in web design, both widely and at the center, is trying to stay current and find the practices that will endure.

The most recent digital project is Teaching History, which offers resources for teaching and learning history. The site uses a content management system and more robust coding practices to create dynamic pages that automatically fill the user interface with content. The visual differences between History Matters and Teaching History are remarkable, and offer the most straightforward demonstration of technological change over time. Technical possibilities, however, are not the only answer for such differences. The purpose of a digital project is inseparable from its technical design. Elements that are used in History Matters remain present in Teaching History; though the format has changed, the content persists.

The digital projects offered through the center are now stratified into three divisions: Research, Public Projects, and Education. The sites I’ve discussed fall mainly into the third category, but similar technical development has marked the progress of collection sites under Public Projects. The early sites that were built before Omeka have similar problems as the early teaching sites, especially in their databases. Both education and collection sites have changed significantly from their early forms, in design and purpose, but have developed along similar lines. Where they go next, of course, is the most interesting question.