Women's Travel Writing

Patricia M.E. Lorcin

Texas Tech University

| |

|

| | Women’s travel writing, long considered the genre of novelists-manqués and second-rate writers, is a rich source for teaching world history. Recent scholarship has swept away old prejudices, and a substantial secondary literature exists on different aspects of this genre, in itself an indication of its growing importance.1 What, then, are its advantages as a source for teaching world history? In the first place, the body of literature is vast, spread over time and space. As early as the 15th century, women were recording impressions of their travels (The Book of Margery Kempe, 1436). Since then, not only have hundreds of women of all nationalities put pen to paper to describe their travels, but they have done so while trekking to every corner of the world.

Second, the background of these writers is varied—from the aristocratic Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who accompanied her husband to Turkey when he took up his ambassadorial post in 1716, to the intrepid Alexander David-Neel, who honed her traveling skills by repeatedly running away from home as a child and went on to become the first Western woman to enter Lhasa, the forbidden city of Tibet.

Housewives, missionaries, settlers, professionals, and sensation seekers have all contributed to existing travelogues so that motivation, social background, gender expectations, and the reception of women’s writing are among the many issues that can be introduced into discussions of the topic. Third, travel literature consists of the impressions of one culture viewing another, and women’s travel literature of one gender viewing others. It is, therefore, an excellent way of introducing concepts of cultural difference and discussing the way in which gender does, or does not, shape perceptions. Finally, travelogues often tell us as much, if not more, about the culture of the author as that of the subject matter, thus making them doubly valuable as sources.

I have used travel writing in different ways in a full range of courses, from the first year survey to the graduate seminar. When I introduce these sources to students in my undergraduate survey, I begin by discussing two concepts pertinent to travel writing: the other and the gaze. Both are essential to understanding the way difference is construed, whether that difference is one of gender, race, nation, or culture. The other is the antithesis of the self and therefore serves an accentual purpose in the conceptualization the self. The gaze, on the other hand, is the way a particular group, conditioned by its gender, national allegiance, social standing or professional class, views the world.

One can therefore talk of the female gaze, the colonial gaze, the Western gaze, etc. My aim is to set the stage for discussions of difference and to do so by using primary sources throughout the course, especially travel texts. Although I use the occasional men’s text for comparative purposes, on the whole I concentrate on women’s texts. I do this to emphasize women’s presence throughout the timeframe of the course. They may not have been in power, but their significance was noteworthy.

The first text I use is an extract from the letters written by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1786) in Turkey. This choice allows me to raise the question of the Ottoman Empire and its relations to the West, to draw attention to the views of an 18th-century aristocratic woman on the Ottoman Empire, and to discuss the importance of letter-writing as a means of private and public communication.

At this juncture I also introduce the concept of the “grand tour” indicating that travel for pleasure was an essentially upper-class European activity in the 18th and early 19th centuries. I then explain that by the mid-19th century women had started to travel for professional reasons, primarily as missionaries. Missionary texts provide a new perspective and open the way for discussions of religious difference and the role of missions in European expansion. 2

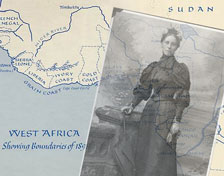

Imperialism is one of the most pertinent topics in relation to travel and exploration. By the end of the 19th century, the spread of European imperialism had made many areas of the world “safe” for women travelers. As a result the volume of women’s writing increased significantly, so there is a wide range of texts to choose from. I prefer to use the work of Mary Kingsley [pictured at left], who traveled to West Africa in 1893 and 1895, and to compare it to male versions of earlier African exploration, such as the works of H.M. Stanley or J. H. Speke.

I am interested in broadening the range of issues connected to travel writing, and such a comparison allows me to do this. These issues include gender; sexuality; race; professionalism; symbolic content; gendering of the text (the feminization or masculinization of the landscape or peoples in it); the personal agendas of the authors; the context and relevance of the work to the larger picture of imperialism or colonialism; and what women did or did not achieve through their work. Of Kingsley’s two works, Travels in West Africa (1897) is more accessible for students.

The masculine tradition of travel writing was considered to reflect public and professional concerns, whereas the feminine tradition was considered to fall into the private and personal sphere. Mary Kingsley’s work belies this stereotype.3 She allied herself with the masculine tradition of producing scientific research, yet she was well aware of social expectations. She adopted a self-deprecating and humorous style to deflect criticism of inappropriate behavior on her part.

Her preoccupation with her dress code is another indication of her consciousness that transgressing the boundaries of femininity was not looked on kindly. On more than one occasion, she emphasizes her femininity while stressing the ambiguity of her situation: “I am a most lady-like old person and yet get constantly called Sir.”4 My students often engage in a lively discussion of the ramifications of gender around such passages.

Her negative attitude toward British colonization and sympathy for the peoples of West Africa are amply demonstrated. This highlights the approach of many 19th-century travelers who were not opposed to imperialism or colonization, but were critical of the abuses engendered by the system. In class, I find that a good way to broach the notion of the female gaze is to examine Kingsley’s detailed descriptions of customs, religious practices, habitat, and dress codes she encounters in her travels. I ask students to select passages that demonstrate her attention to detail and then we share the passages in class. I ask them to tell me how the passage they have selected demonstrates a particularly female gaze, as opposed to a male gaze. This approach works well both as a means to teach deeper reading into a complex text, but also to focus attention on the gendered nature of the text.5

In addition to these two texts, women’s travel literature can be used successfully for any period, including the present. This genre of literature teaches students to analyze a text in relation to both the author and the subject and introduces the concept of a gendered text. It helps students realize that the literary merits of a source are often secondary to its sociological content and that travel writing as a textual representation can be extremely useful if approached properly.

The main problems students encounter are related to details, as many texts assume that the reader is familiar with the terrain around which the narrative is constructed. Kingsley’s work, for example, refers to peoples of West Africa such as the Fan, Igalwa, and Bubi, and to geographic areas that students might not find familiar. I provide brief explanations of the different peoples and short definitions of unusual terms or vocabulary. Having used these sources for a range of courses, I have learned to adapt them according to the course level and subject matter. In all cases, I have found that students’ responses to these sources are very positive.

_________________________

1 See for example Dea Birkett, Spinsters Abroad: Victorian Lady Explorers (Oxford, 1989) and Amazonian: The Penguin Book of Women’s New Travel Writing (London, 1998); Sara Mills, Discourses of Difference: An Analysis of Women’s Travel Writing and Colonialism (London, 1991); Jane Robinson, Wayward Women. A Guide to Women Travellers (Oxford, 1991); Billie Melman, Women’s Orients. English Women and the Middle East 1718-1918 (London, 1992); Catherine Barnes Stevenson, Victorian Women Travel Writers in Africa (Boston, 1992); Susan Morgan, Place Matters: Gendered Geography in Victorian Women’s Travel Books About S.E. Asia (New Brunswick, N.J., 1996); Bénédicte Monicat, Itinéraires de l’écriture au feminine (Amsterdam, 1996); Indira Ghose, Women Travellers in Colonial India: The Power of the Female Gaze (Oxford, 1998); June Edith Hahner, Women Through Womenös Eyes. Latin American Women in 19th-century Travel Accounts (Wilmington, Del. 1998); Cheryl McEwan, Gender, Geography and Empire. Victorian Women Travellers in West Africa (Bloomington, 2000).

2 For extracts from women missionaries’ writings see Patricia W. Romero (ed.), Women Voices on Africa. A century of travel writings (Princeton, 1992). For a discussion of women missionaries in the Near East see Melman, Op. Cit.

3 Her second work, West African Studies, published in 1899, was a scholarly approach to the subject into which she incorporated information from both her voyages to the area including material that had been excluded from Travels in West Africa.

4 Mary Kingsley, Travels in West Africa (London: Thomas Nelson, 1965, 3rd edition) p. 502

5 A website that contains other materials on Kingsley, including audio recordings and a map of her travels in West Africa is at: | |