|

|

|

One of the first questions historians ask when analyzing documents is: “Who is the author?” The author is often seen as a historical actor with goals or experiences that shape the document. Is the author male or female?  An identifiable member of a minority or majority ethnic group? A possessor or a pursuer of political power, economic wealth, or social status? What is the author’s purpose in writing the document? To what extent does the document provide an accurate insight into events? This kind of information can provide a starting point for analysis. An identifiable member of a minority or majority ethnic group? A possessor or a pursuer of political power, economic wealth, or social status? What is the author’s purpose in writing the document? To what extent does the document provide an accurate insight into events? This kind of information can provide a starting point for analysis.

But what if the author is not an individual? What if the author is a national government, a corporation, a legislative body, or a United Nations commission? How does this affect historical analysis? These official and often “authorless” documents are staple features of all societies. They include government reports and laws, press releases, diplomatic communication, and local policy statements. How should historians respond to these authorless documents? If they have no author, can we assume they have no bias?

Many of these writings are pretty bland in their language. Lively events are submerged in legalistic language and stripped of emotion. If you came “cold” to the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I, would special terms such as the "war guilt clause" leap out at you as an obvious basis for future grievances and fuel for a political movement? Authorless documents present a different set of issues for analysis than do those authored by individuals.

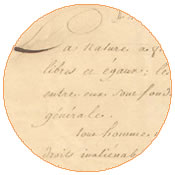

Even without an identifiable author, these documents are still historically constructed writings ripe for careful analysis. By understanding the nature of the processes that resulted in a particular authorless document, historians are able to mine these sources for more information than might be apparent to the novice reader. For example, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was the result of a long, drawn out negotiation among many contending parties in the French National Assembly in 1789. As evidence of these compromises, historians point to the provisions calling for liberty and those calling for property rights. The sweeping declaration of personal liberty was a demand of the more radical members of the Assembly, while the guarantee of property rights satisfied the more conservative members. Paying attention to nuances such as these gives historians important clues into the underlying nature of these official documents.

|