|

|

|

|

Official documents exist for a wide variety of reasons. Sometimes the identity of a writer is deliberately concealed. In other situations, documents are produced by committees whose members claim joint authorship, or the documents are negotiated among a number of groups or governments. The common practice is to say that “the government said” or “the committee decided,” treating documents as historical actors that decree or demand even though we have great difficulty saying exactly who is involved.

The first step, then, is to ask who created a document. Is the work attributed to an individual, or is it the presentation of a committee, an organization, or a government? What does the document say about its origins? Is it signed? If the statement appears to be authorless, try to figure out what it claims to be. Then ask yourself if the statement has additional clues. Are you looking at a treaty, a diplomatic note, or an instruction to an embassy? The answers to these questions help establish the direction of your analysis.

The identity of an author may be deliberately concealed from view. For example, a national government official may publish an article in a major journal such as Foreign Affairs or be quoted “off the record” in a newspaper. Sometimes an organization does this in an effort to test reactions to an upcoming policy initiative or provide the rationale for a policy already in place. The article may be signed “Anonymous” or “X,” while the news source may be identified as a “high-ranking” official. The goal of this approach is to prevent recrimination against the author or the government in case of negative public or international reaction.

In other cases, a document is signed by a committee or by committee members. The individual preparing the document tries to capture the “sense” of the committee. While the “known” writer may have been influential, the committee perspectives also shaped the final document. The press releases and other documents produced over the last half century by the African National Congress are frequently presented as the work of committees. Today, the ANC website adds the notation that Nelson Mandela was present or approved of the statement. This attribution should not be taken as proof that Mandela, the former president of South Africa, actually wrote each of these statements, but they do imply his agreement with the views expressed in the document.

| |

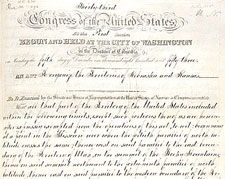

When working with official documents, we often start with a definable document over which no individual can claim authorship. Congressional bills, for example, often begin but do not end up with identifiable authors. A bill, once introduced, goes to a subcommittee for review and, if approved there, goes on to a committee for further review or modification. Once the bill reaches the legislative floor it may be further modified by amendment. If it passes, the bill goes to the other branch of Congress that repeats the process of review and amendment. Then, in many

|

Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) |

|

cases the two different versions of the bill—the one that passed the House and the one that received Senate approval—have to be reconciled by a conference committee. New features are often added during the conference.

In this example of the legislative process, there generally is an identifiable “author” of the bill—members of Congress and their staffs—but the final product is the result of a process that may have amended the bill into a form that bears little resemblance to the original proposal, even though the legislation may still be known as the Smith-Jones Act. The process involves many actors and many decision points. Along the way there were lobbyists who initiated or modified the proposal, congressional staffers whose understanding of the issues helped shape the language of the law, and congressional representatives who agreed to support the bill only if it contained an extraneous provision of interest to voters in one state or district or to a special interest group. While it is often possible to identify the person who inserted a particular provision, there is no clear author for the totality of the measure.

The same issues of analysis apply to other kinds of organization. Corporations often “speak” as legally constituted entities (in contrast to small business owners, who are readily identifiable as the voices of their own companies). This is true because public corporations are owned by stockholders who have no role in daily management. Indeed, the owners (stockholders) do not directly authorize specific actions of a company except at rare moments when they are asked to approve the decisions of executives at stockholder meetings. They reach their decisions through bureaucratic processes that try to account for all of the different areas of corporate activity and concern. Similarly, churches often speak through councils that issue their statements collectively.

The United Nations (UN) provides another good example. One of its best-known measures is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). The Declaration states that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world.” Who wrote this statement? The UN description of this passage of the declaration refers to Eleanor Roosevelt, an inspiration for the declaration, and Mary Robinson, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in 1997. Overall, though, it presents nations rather than people as the prime actors in its development. Thus, passage of the Declaration is portrayed as the result of widespread consensus.

We rarely refer to these official documents as “authorless,” saying instead the Smith-Jones Act or the UN declaration; that the church “said” or Congress “passed” a resolution. Remembering the difference between the historical actions of individual actors and the processes created by people working in groups is important, even though this approach separates individuals from the processes they create. This elimination of an identifiable writer of a document does not make the document neutral—but neither does it mean that the agency that produced it can be automatically regarded as an author comparable to human authors.

|

|