Some Curiosities of Modern Photography. Part II.

By William G. FitzGerald.

|

The mule's head was to be blown off with dynamite, and the wires that conveyed the electric current to the cartridge round the animal's neck were also employed to produce a simultaneous action of a photographic shutter. A seen in the accompanying reproduction, the mule is just about to fall, and the rope by which it was tied to the stake has not had time to show the slightest movement.

|

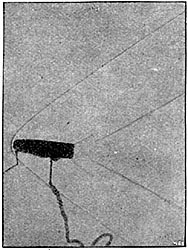

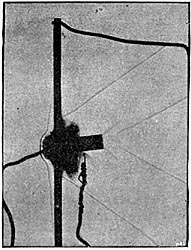

A word concerning the electric spark used by this scientist is absolutely necessary. Not only did such sparks as were used by Lord Rayleigh and Professor Worthington last much too long, but a spark that was extinct within the 7-1,000,000th of a second was hardly suitable for bullet photography. Professor Boys first provided an electric spark whose duration was rather less than the I-10,000,000th of a second; in other words, that duration bore the same proportion to a second that a second does to four months. While this spark lasts, a bullet from a magazine rifle, travelling at the rate of 3,000ft. in a second, cannot go more than 1-400th of an inch. Professor Boys set up his apparatus in one of the passages of the college. The bullets were received in a box of tightly packed bran, five feet square, after having passed through an old packing case; and the spark was produced by the projectiles themselves severing some fine lead wires and thus completing the circuit. No camera entered into the experiment. Martini-Henry and Service rifles firing cordite ammunition were used; also a choke-bore sporting gun, and a rifle carrying an aluminium ball whose speed was 2,000 miles an hour.

Now, I have no desire to puzzle my readers with elaborate descriptions of Professor Boys' electrical apparatus; therefore, I will simply say that the photographs here given, resulting from the experiments, are only photographs of the shadows of the bullets.

|  |

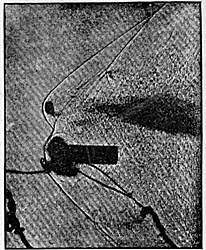

The air waves caused by the bullets are clearly defined; and in that photo. which shows a plate of glass being struck, one may see the splinters flying backwards (Fig. 3). As in the case of falling drops, Professor Boys took photographs of various stages of flight. In one picture is seen the magazine bullet immediately after having passed through the glass; it is thickly coated with bristly particles (Fig. 4). A little later on we see it comparatively clear of glass splinters, but accompanied by the piece punched out on the first contact. This piece of glass has an air wave all to itself, and is evidently bent on accompanying its liberator (Fig. 5). A discharge from a shot gun is depicted in Fig. 6. The wad is seen behind the shower of bullets.

Now, I have no desire to puzzle my readers with elaborate descriptions of Professor Boys' electrical apparatus; therefore, I will simply say that the photographs here given, resulting from the experiments, are only photographs of the shadows of the bullets.

|  |

I may say that the photography of projectiles commenced shortly after the Crimean War, when experiments were conducted by the War Department at Woolwich Arsenal. That was in 1858. Wires were placed across the muzzle of a mortar throwing a thirty-six inch shell (the "Palmerston Pacificator"), and a photograph of its flight was electrically obtained.