The Beatles, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Elizabeth L. Wollman

Baruch College

| |

|

| | Between the mid-1960s and early 1970s, many rock acts began to devote less time to live performances and more to mastering the rapidly developing studio technology with the aim of making increasingly sophisticated sound recordings. This shift from concert hall to recording studio was roughly simultaneous in the United States and the United Kingdom, with the release of albums like the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds (1966) and the Beatles’ Rubber Soul (1965) and Revolver (1966). Such newfound familiarity with the workings of the recording studio allowed for greater artistic control, which, in turn, allowed rock musicians to move beyond the perceived limitations of the sound recording.

One result was the recording known as the “concept album.” The question as to who owns the claim to the very first concept album is a matter for much debate among popular music scholars and aficionados. Yet in my courses on the history of Western popular music, I find that the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band serves as the most straightforward and appropriate example to discuss with students.

Released in both the United States and the United Kingdom in June 1967, Sgt. Pepper’s quickly went multi-platinum, spent 15 weeks at number one on the Billboard album charts, and remains one of the highest-selling records in history. Conceived as a unified entity, the album lacks traditional divisions between its 13 songs, each of which segues smoothly into the next, and all of which are loosely linked by the reprise of the title song near the end of the album, as well as by a number of imaginative studio effects. Largely interpreted as an homage to psychedelia, the album features recurring themes including role-playing (e.g., the title song); the generation gap (e.g., “She’s Leaving Home”); and the creative freedom (and excessiveness) of the late-1960s youth culture (”Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”; “Within You Without You”; “A Day in the Life”).

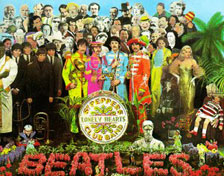

Many of these themes are detectable not only on the album’s songs, but in its packaging as well: Sgt. Pepper’s features elaborate cover art designed by pop artist Peter Blake in which the colorfully costumed Beatles pose in front of a collage of public figures that the group had listed as “people they’d most like to have in the audience at [their fictional band’s] imaginary concert.”

In my semester-long course on Western popular music, students explore the sociopolitical, economic, and technological factors that have influenced the development of the music from the mid-19th through the 20th century. I usually lecture on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band approximately halfway through the semester, at the end of a section on the 1960s. Prior to this section, emphasis has been placed on the economic and socio-cultural aspects of mid-1950s to mid-1960s rock ‘n’ roll: the music’s relationship to the New York music publishing industry commonly known as “Tin Pan Alley”; its connections to race and class; and its impact on the generation gap. \

When it comes to discussing rock music from the late 1960s to the present, among the topics I focus on are the growth of the music industry and the subsequent, increasingly complex relationship between art and commerce.

Introducing Sgt. Pepper’s when I do proves immensely rewarding. It helps my students grapple with these issues, in large part because the record is an artistic and commercial landmark that reflects the technological advances of the day. That it manages to capture the complex sociopolitical mood of the time is an added bonus.

Students are not required to listen to the album in advance of the lecture, but a majority are usually at least somewhat familiar with it before it comes up in class (contemporary lore about post-Gen-X youths being surprised to learn that Paul McCartney was in a band that existed before Wings does not ring true in my experience). Prior to discussion of the album, however, I assign readings on some of the sociopolitical issues of the time and discuss ways that these issues influenced popular music.

When I commence discussion on Sgt. Pepper’s, I pass the LP around while listing some of its remarkable aural and visual features: the album required hundreds of hours in the studio and made use of studio technology so advanced that the music would have been unable to reproduce in a live setting; that it was the first LP to feature a “fold out” cover that opened like a book and the first to feature song lyrics printed in full on the back of the jacket; that original copies of the album featured inserts of paper-doll Beatle cutouts; that the record featured such odd touches as a chorus of gibberish etched into the playout groove (the final groove in the record that causes the tone arm to rise) and a single note at the end of the album played at 20,000-Hertz frequency, thus audible only to dogs.

Time constraints prevent me from playing the entire album in class, although I encourage students to do so at home, explaining that its many subtleties benefit from careful listening—particularly on headphones. During class, we focus on “A Day in the Life,” which I feel comprises many of the album’s themes, is exceptionally produced, and stands out as a sensitive, intelligent commentary on a vastly complex historical period.

Before we listen, I hand out copies of the song lyrics and explain some of the purported influences on Lennon’s creative process. Lennon allegedly based his section (McCartney wrote—and sang—the bouncier middle section) on articles he read in the London Daily Mail for January 17, 1967. The first verse interprets an obituary for Tara Browne, a wealthy friend of both the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, who had driven his car into a van in December 1966. The final verse refers to an article in the same edition about the number of holes in the road in Blackburn, Lancashire, which allegedly struck Lennon as appropriately absurd.

Before playing the piece, I explain some of the topical language (”I’d love to turn you on”; “He blew his mind out . . .”), and advise the students to listen carefully, not only to the lyrics, but to some of the many perceptible studio triumphs (e.g., the way Lennon’s voice “travels” from one speaker to the other and back again; the orchestral glissandi and final chord, which were recorded separately, then manipulated and linked in the studio; the nonmusical sounds—like the ringing alarm clock, sharp inhalations and exhalations of breath, and the counting backward from ten—that can be heard during the piece). Finally, students are told to listen especially carefully for barely perceptible extramusical sounds beneath the sustained final chord: the squeak of a chair in the studio and a subsequently uttered “shhh!”

I try to gear class discussions that follow the playing of “A Day in the Life” toward ways that the song reflects the period, as well as the ways it exemplifies late-20th century technological advances and their influence on the mass media. Usually, before we listen, I ask the class to think about ways that the song’s technology and lyrics relate to the Beatles’ world. Depending on the common interests of the students with whom I am working, class discussion tends to gravitate strongly toward one topic or the other. Thus, when I played the song for a group of theater, dance, and graphic design majors at a tiny liberal arts college, there was more collective interest in the music’s relationship to the sociopolitical issues of the period, and less of a common grasp of the record’s technological aspects.

On the other hand, when I play the song for students at Baruch College, a business college where most music majors are business-minded and music industry bound, the sociopolitical implications of the recording usually seem less interesting to students than discussions about the album as “artistic commerce” or “commercial art,” as well as about its role in redefining the relationship of popular music to its primary medium of dissemination: the sound recording.

Regardless of the setting, however, students tend to react enthusiastically to the lecture and listening exercise. Regardless of the setting in which I have taught Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, students tend to respond with glee to the many aural “tricks” that they are told to listen for. Even if they get nothing else out of the lecture, a majority of students seem especially thrilled to listen for and to hear the squeak of the chair and the subsequent “shhhh” at the very end of the record. | |