Ernest Brennecke, looking back on the rise of the comic strip from the

vantage point of 1924, praises the comics for representing "true things"

rather than the "pursuit of the good and beautiful." Gilbert Seldes,

in a book on the aesthetics of popular culture published in the same year

as Brennecke's essay, defines comic strip realism similarly. In support

of the assertion that "none of our realists in fiction come so close

to the facts of the average man," Seldes notes that "the comic

strip…is…more violent, more dishonest, more tricky and roguish,

than America usually permits its serious arts to be." Comic strips

expose the illusions of the "life of the average man" because

comic strip characters "have so little respect for law, order, the

rights of property, the sanctity of money, the romance of marriage, and

all the other foundations of American life, that if they were put into fiction

the Society for the Suppression of Everything would hale them incontinently

to court and our morals would be saved again" (Seldes 197, 201).

Taken together, Brennecke and Seldes present a remarkably coherent vision

of the comic strip as a realist deflation of bourgeois illusion. Coherence

disintegrates, however, when these critics address the fact that many strips

contain elements so far removed from realism as to deserve the label "fantastic."

Brennecke acknowledges that some realist cartoonists resort to "wonder-geography"

and talking animals, but he dismisses fantasy as a temporary vacation spot

for the imaginations of artists who are "a little tired and in need

of fresh inspiration" (674). Gilbert Seldes draws the distinction between

realism and fantasy more sharply when he writes, "At the extremes of

the comic strip are the realistic school and the fantastic," identifying

George Herriman's Krazy Kat as the best example of the latter genre.

And while Brennecke sees the fantastic in comics as a relatively minor offshoot

of the form, Seldes sees the fantastic in Krazy Kat as the element

that lifts it above the rest of the "vulgar" comic strips into

the realm of high art. Herriman's work is, according to Seldes, "rich

with something we have too little of--fantasy (203). Diverging from both

Brennecke and Seldes, columnist William Bolitho identifies all strips as

fantasy: "These interminable stories are indeed like an immense system

of burrowings in the world of fantasy and imagination" (34). While

all three authors identify an element of fantasy in the comic strips, they

disagree wildly over whether fantasy departs from the essence of the form,

elevates it, or defines it.

This disagreement is more a function of a strange duality in the comics themselves than of any error on the part of their critics. Throughout their rich history the funnies have aimed both to manufacture illusions and to puncture them. While bad boys and low-lifes like the Katzenjammer Kids, Mutt, and Calvin display an irreverent disregard for the illusions of manners, genteel pretension, or the idealized family, dreamers like Little Nemo, Little Orphan Annie and (again) Calvin live in a fantasy world of wish-fulfillment. I propose that the incoherence of comic strip realism as a genre points back to a central contradiction in turn-of-the-century American market culture. Reality and fantasy are two sides of a coin that turns up repeatedly as subject and subtext in the comic strips: the urban marketplace. Because the comics originated in the urban press, the city occupies a crucial but ambiguous position in their mythology. Comic strips represent the city both as an especially real place, the site of the "bottom line" of class and commerce, and as a dreamland of wish fulfillment.

The city has stereotypically served as a privileged site of the real, a noir world beyond the illusions of innocence and romanticism. But the reverse is equally true: the flip-side of the city's reality is its unreality. Amy Kaplan's ground-breaking study of American literary realism uncovers this side of the city by describing realism as an attempt to contain a sense of unreality generated by accelerating social change in the urban environment. Jackson Lears similarly argues that the disturbing sense of groundlessness associated with modernism can be traced in part to the unreal chaos of urban experience. But while both of these writers insightfully highlight the city's status as site of the unreal, I would argue that they fail to offer an adequate historical explanation for the persistence of the trope of the unreal city in American culture. Urban unreality is not simply a result of the rapid social change involved in the explosive urbanization of the nineteenth-century. Rather, the unreality of the city arises as the necessary counterpart to the reality of the city, the contradiction between urban reality and urban unreality reflecting a contradiction at the heart of market-culture itself.

In the turn-of-the-century comic strip, representations of the urban marketplace rock between the trope of the city as gritty reality and the trope of the city as decidedly unreal dream-realm of wish fulfillment. On the one hand, comic strips represent urban commerce and the demands of the market as the bedrock of reality underlying all idealistic and moralistic illusions. On the other hand, the urban marketplace strives to fulfill the fantasies of its resident consumers, as does the comic strip, and so the city becomes a surreal amusement park run mad.

|

� �

|

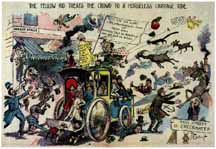

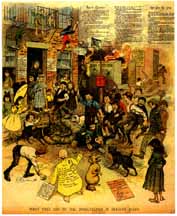

The comic strip credited by many historians as the starting point for the genre provides a perfect example

of the ambiguous line between journalism and fiction in the comic strip's

early days. R. F. Outcault's Yellow Kid (named for his yellow nightshirt)

presented readers with a portrait of a ghetto resident that its author claimed

to have drawn from life. In an interview for The Bookman magazine

Outcault tells us, "The Yellow Kid was not an individual, but a type.

When I used to go about the slums on newspaper assignments I would encounter

him often, wandering out of doorways or sitting down on dirty doorsteps.

I always loved the Kid. He had a sweet character and a sunny disposition,

and was generous to a fault."

The Kid is real to Outcault partly because Outcault has met real kids very much like him. But Outcault's choice of the street kid as the subject for his strip also suggests that when the newspapers tried to package the reality of the city, some parts of the city and some of its inhabitants counted as more real than others. Outcault uses a fictional representation of the working class to create a distinction between a genuine city and a superficial city. The claim that the Kid is real carries more weight because the Kid himself delights in exposing the reality underneath the illusions of authority.

A joke told by Outcault during the Bookman interview nicely illustrates the extent to which his satiric imagination depends on class constructions.

Before I let a joke go out of my richly furnished studio I always try it on some one to see how it goes. Usually I have my butler call all my servants into my studio-the coachman, the cook, the laundry-maids and the chamber-maids, my valet and the man who cares for my golf sticks. After they are all assembled I explain to them the joke, being careful to avoid putting my own very humorous personality into it and letting the joke stand for itself. They usually roar with laughter, when suddenly it occurs to me that, perhaps, they do so because I pay them their wages. Then comes in the man with the wash bill, and that puts an end to everything humorous. Seriously speaking…

The punch-line of this scene is the intrusion of power relationships and financial necessity (wages and bills) into the employer's pretension to humor, a punchline that depends on the perspective of servants who pretend to be more amused than they are. Outcault's implied understanding of this perspective grants him a certain authenticity, for the servants' heightened awareness of material considerations, based in their own material need, makes their position undeniably genuine.

|

|

Some comic strip artists laid claim to a similar working-class authenticity by representing themselves in the position of employee. When Frank Willard, author of Moon Mullins, narrates a scene from his workplace, he portrays himself as a rowdy underdog much like the Yellow Kid. He becomes, in effect, the "tricky and roguish" character cited by Gilbert Seldes as the quintessence of the comic strip.

I worked for a syndicate manager once who got everybody in the place together once a week and jumped on a desk and gave us "pep talks." He didn't give us ideas, but, oh boy, how worn out we were after those pep talks. The guy that applauded the loudest got the most money, and I didn't get much as he found out who it was who gave him the bird.

--Frank Willard, as related in Sheridan (75)

When Brennecke locates the truth of comic strip realism in the comics' habit of "commenting trenchantly" on "the life of the middle classes" (Brennecke 667, 673), it is comics like the Yellow Kid and artists like Willard that he has in mind. This deployment of a rowdy "reality" with a class subtext suited the ethos of the papers Outcault worked for, and so demonstrated that class was only one half of the economic reality that undergirded comic strip realism. The other half was commerce. Michael Schudson notes that papers like The Journal and The World emphasized self-advertisement, openly acknowledging that readers paid their money to be entertained and that the publishers were out to sell papers. Features like Outcault's sold papers, and newspapers like The New York Times scorned the comics if they wished to position themselves above vulgar self-advertisement and the crass money-grubbing of circulation wars. Humor magazines competing with the comic supplements similarly pulled class on the yellow papers, while the yellow papers in turn used the low as a base from which to attack their rivals.

� �

|

� �

|

� �

|

� �

|

� �

|

� �

|

� �

|

Any city gives a map of the psyche, a quantitative account of the strength and complexity of the system of human desires at a given cultural moment. How much provision for sitting and watching, how rare and peculiar the variety of flowers or prostitutes for sale, how large the living rooms of apartments…compared to public spaces for entertainment…the city is the visible account of the balances and imbalances of the psyche.

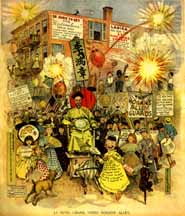

McKay's strips bring out this aspect of the city not only by placing realistic urban settings in the context of dreams, but also by mirroring a part of the city devoted with special intensity to wish-fulfillment--the amusement park. Scenes like these recall the rides and electric splendor of Coney Island. As John Kasson notes in his history of Coney Island, electric lighting constituted a crucial attraction to Coney Island's night life. The lights and exotic architecture helped to create, in the words of Luna Park's designer Fredrick Thompson, "a different world--a dream world, perhaps a nightmare world--where all is bizarre and fantastic…" A world, one might add, within which customers could feel free to pursue and purchase their heart's desires. If, as Fisher suggests, the city is a map of the psyche, then Coney Island was the dreamspace within which New York City played out the whims of its id. McCay clearly borrowed from the architecture and ambiance of Coney Island when he constructed his own dream realm.

�Slumberland shared more than just a glowing skyline with Coney Island; it also shared the fantastic appeal to consumer desire. The consumerist dimension of McCay's fantasy reveals itself in a crucial episode in the early Little Nemo strips. The first several strips depict Nemo as an unwilling visitor to a half-nightmarish world, and the child has not yet reached Slumberland proper, the administrative center to the empire of his dreams. Only when Nemo visits Santa Claus' toy warehouse, where he is told that he can eat as much candy as he wants, does he give himself over to the surreal experience of his own dreams. When he wakes up from this episode he expresses, for the first time, regret that he has been released from sleep, rather than relief. He never meets Santa himself--the toys and candy effect his conversion, not their maker. Nemo's new openness then facilitates his progress, and soon after this episode he reaches Slumberland itself. Not that Nemo's acceptance of the journey implies the journey's end: in Slumberland, as in the world of the consumer, there is always some new object of desire to pursue. Once within the boundaries of Slumberland Nemo must then make another trek to meet the princess of Slumberland, and then he and the princess start out together for yet another journey to meet her father, King Morpheus. The center of Slumberland is always receding.

� �

|

For a brief period from 1901 to 1902, after he had already discontinued the Yellow Kid, Outcault also experimented with Harris-inspired fantasy in the form of a strip called "Lil' Mose." While some of Lil' Mose's adventures involve encounters between the black community and white authority, by the end of his tenure on the Sunday supplement Mose had left his home culture and its authority structure entirely. Later "Lil' Mose" cartoons detail his rather inexplicable journey to New York City, where he functions less as a member of an oppressed class than as an utter alien. Rather than revealing the "real city," Mose's point of view defamiliarizes it. For him the city is a fantasy realm. But if the city seems like a fantasy to Mose, he seems equally fantastic to the urbanites in the cartoons, in part because he is accompanied by a troop of talking animals.

� �

|

� �

|

A fox don' like ter steal, he wouldn't lie nor cheat.

but foxes is like folks…dey certain'y mus' eat.

An folks don' never send him geese nor any kin' ob game.

So he's got ter go an git it an a coon is jes' de same.

Recalling Luks' cartoons about Uncle Remus' poaching, Outcault offers what Alan Havig too generously calls a "commentary on the stereotypical behavior which whites ascribed to blacks" (34). But even in this cartoon which emphasizes so clearly the talking animal's role as an allegorical figure for the poor African American, the mystically idyllic scene in the lower right hand corner hints at the possibilities of the subaltern realm for pure imaginative escape. As Mose gathers with his animal friends under the moon, he acquires an otherwordly quality through his contact with such fantastic beings even as they become a realist allegory through their identification with his class position.

Once Mose leaves the imagined southern social structure that defined his status and heads for the city, the incipient fantasy of his earlier rural idylls achieves its full force. The reactions of New Yorkers reveal that he and his animal friends have a certain value as spectacles of pure magical aberration. Mose plays with a black mermaid at Coney Island while the natives gape so broadly at the animals that "you'd think dey'd break dere face."

� �

|

� �

|

� �

|

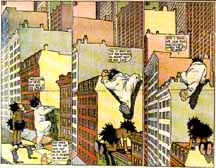

Miles Orvell, in the process of evaluating the "posthistoricism" of Jay Cantor's novel Krazy Kat and Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus, critiques this aspect of Herriman's fictions when he writes, "In creating a self-contained aesthetic universe largely impervious to history, Herriman's strip seems essentially modernist, the product of an imperial imagination" (112). In the light of the genealogical relationship I've outlined here between Coconino County and New York City via Hogan's Alley, it seems inaccurate to call the universe of Krazy Kat "impervious to history." Coconino County draws much of its meaning from a tradition of representing working-class worlds in the comic strip. Orvell hits closer to the mark when he implies a critique of Krazy Kat on the grounds of its postmodernism, rather than its modernism. The final moral of the story Orvell tells about Cantor and Spiegelman is that these two authors, although writing in a postmodern vein, manage to bring the reader "back into the catastrophes of twentieth-century history in a way that calls for a healthy self-interrogation and self-renewal along with a reckoning of guilt and that takes us finally well beyond the usual pastiches of postmodernism and the forever disappearing self" (126). Krazy Kat, in addition to its crimes of modernism, also "anticipates the promiscuous confusions of postmodernism" (112) and so perhaps could be accused of the sort of pastiche that Orvell interprets as an attempt to escape from history. Orvell notes the characters' "dialect that fuses eclectically ethnic accents," the "destabilized desert spaces" and "surrealistic vocabularly" of the strip's graphic style, and "Krazy's androgyny." All of these elements are indeed present in Krazy Kat, all hint at pastiche and the "disappearing self," and all accentuate a decontextualization that removes the comic strip underdog from any class history.

We could blame this facet of Krazy Kat, and of comics in general, on the commodification of class issues and their absorption into consumer culture, corporate culture, the culture industry, and, ultimately, "the cultural logic of late capitalism." This take on postmodernism in general is best expressed in Fredric Jameson's Postmodernism, and it has been answered by such writers as Linda Hutcheon, who has argued that the techniques and genres critiqued by Orvell and Jameson can, in fact, be made to serve historicist purposes.

It would deprive Krazy Kat and the comic strips in general of their historical voice, however, to critique them solely within the context of our contemporary debates about postmodernism. Herriman's own comments about his strip point toward an alternative interpretation of the strips tendency to abstract their class representations into decontextualized fantasy worlds. There is something compelling in Herriman's assertion that the strip "jes' grew." It recalls Ishmael Reed's later use of the phrase in his undeniably postmodern novel Mumbo Jumbo. In Reed's novel (dedicated to Herriman, among others) "jes' grew" is an epidemic "disease" that strikes the States at the dawn of the Jazz Age, moving its victims to dance provocatively and to live with abandon. He writes, "if the Jazz Age is year for year the Essences and Symptoms of the times, then Jes Grew is the germ making it rise yeast-like across the American plain" (20). This Jes Grew comes out of the nowhere of the popular, but, in spite of its origins in the small and unimportant, builds such energy that it dominates the age. Like Reed's fantasy, the unreality of Krazy Kat and the comic strip in general can be read as a measure of its liveliness rather than a measure of its bad faith. It shows us the utopian side of a popular culture born in the marketplace, a fantasy that grows out of commercial culture but promises to transform it and acquire a life of its own. It offers the hope that the diminuitive will have its revenge.

The fantastic side of this utopian allegiance to the cultural underdog may be more pronounced in Herriman's work than in other comic strips, but its conflicted bonding of the real to the unreal and material necessity to desire ultimately characterizes the history of the strips. Born in the yellow press and partaking of its frank approach to money and business,the strips built the foundation of their humor on the commercial "underside"of the city. But commerce is not just the material reality of the urban environment. It is also the medium of desire. And so images of economic and class reality constantly transform into fantastic images of escape andwish-fulfillment, in the comics and in the larger culture of the marketplace.