Understanding Advertising

Michael O'Malley, Associate Professor of History and Art History, George Mason University

Introduction

This exercise teaches how to read documents that depend heavily on images for their effect. It focuses on advertising in the 1920s, an important period in the development of modern advertising.

Advertising has a long history in the US, but professional "Ad agencies" don't appear till the late nineteenth century. The first agencies concentrated heavily on patent medicines, an unregulated field in which manufacturers made elaborate claims.

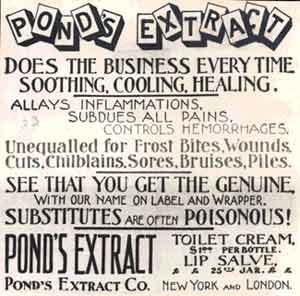

The

example on the left is from 1898. It claims a wide variety of cures thanks

to its unexplained "extract." The ad is calculated to catch

the eye, with its headline, but spends most of its space listing the product's

virtues and warning against counterfeits.

The

example on the left is from 1898. It claims a wide variety of cures thanks

to its unexplained "extract." The ad is calculated to catch

the eye, with its headline, but spends most of its space listing the product's

virtues and warning against counterfeits.

Besides capitalizing on worries about health, ad agencies early on recognized that people were anxious about social status--about appearing prosperous or comfortable, wealthy and "up to date. The ad below, also for "Pond's Extract," comes from 1915. By then, it had become easier (and cheaper) to include illustrations in mass advertisements.

Historian Roy Rosenzweig concludes that in the 1910s and particularly the 1920s, advertising agents focused their attention on identifying—and often inventing—personal anxieties that could be resolved by the purchase of specific products. “Advertising,” wrote one commentator in a trade publication, “helps to keep the masses dissatisfied with their mode of life, discontented with ugly things around them. Satisfied customers are not as profitable as discontented ones.” Advertisers, as historian Stuart Ewen notes, tried to endow people with a “critical self-consciousness” directed especially at their personal appearances.

That was the strategy followed, for example, by Odo-Ro-No, a deodorant for women, which in 1919 became the first company to use the term “B.O.” (meaning, but not saying, “body odor”) in an advertisement. Previously, deodorant ads had confined their pitch to suggestions about how they would foster daintiness and sweetness. But Odo-Ro-No took a much more direct approach, telling potential customers to take the “Armhole Odor Test” and warning them that social success hinged on eliminating B.O.

Listerine mouthwash took a similar approach. The Lambert Pharmaceutical Company had developed the antibacterial liquid back in the 1880s, and it was long sold as a general antiseptic. After World War I, the company sought to expand its market. Advertising man Gordon Seagrove recalls being called in by the Lambert Brothers to discuss how this could be done. The company’s chief chemist was enlisted to describe the product and its uses. “As he read along in a singsong voice,” Seagrove remembers, “he mentioned halitosis. Everybody said ‘What’s that?’” Learning that it referred to “unpleasant breath,” they immediately thought “maybe that’s the peg we can hang our hat on.”

Although

there was some worry about whether such a “delicate subject”

could be handled in magazines and newspapers, Seagrove and his collaborator,

Milton Feasley, launched an ad campaign that played heavily on fears about

how others would react to a halitosis sufferer. The most famous of their

ads concerned the “pathetic” case of “Edna,” who

was “often a bridesmaid but never a bride.” She was approaching

the “tragic” thirtieth birthday unmarried because she suffered

from halitosis—a disorder that “you, yourself, rarely know

when you have it. And even your closest friends won’t tell you.”

Tragic Edna can be seen on the right.

Although

there was some worry about whether such a “delicate subject”

could be handled in magazines and newspapers, Seagrove and his collaborator,

Milton Feasley, launched an ad campaign that played heavily on fears about

how others would react to a halitosis sufferer. The most famous of their

ads concerned the “pathetic” case of “Edna,” who

was “often a bridesmaid but never a bride.” She was approaching

the “tragic” thirtieth birthday unmarried because she suffered

from halitosis—a disorder that “you, yourself, rarely know

when you have it. And even your closest friends won’t tell you.”

Tragic Edna can be seen on the right.

In response to the ad campaign, Listerine sales went from $100,000 per year in 1921 to more than $4 million in 1927. Meanwhile, the strategy of ads as “quick-tempo socio-dramas in which readers were invited to identify with temporary victims in tragedies of social shame,” writes historian Roland Marchand, led to a new “school of advertising practice.”

Updated | April 2004