|

A personal account rarely is written without particular motivation—every account has some agenda. Always consider why the subject feels it is important to share his or her life either privately or with an anonymous public. The narrator’s motivation will account for what parts of a life are discussed and what details are filtered out.

What motivated the author of the personal account? A mode of address, details of place and time of writing, and the structure of the account itself may all offer clues. Whether written or oral, a personal account is a subjective, selective account of a life recorded for a specific purpose, ranging from personal catharsis to revisionist history.

Was the account solicited or freely given? Is the motivation coming from the narrator or the recorder? If the account is written privately, the information contained in it is likely to be more personal, detailed, and indicative of private thoughts and emotions. If the account is gathered in an interview format with a scholar who is not well known to the subject, it is likely to be more formal and general.

If the subject writes an autobiographical account intended for publication, he or she has consciously selected particular incidents for public consumption. Although some private thoughts may be included, this kind of account will not be as intimate as the diary form. If a scholar solicited the story, rather than finding the account, the scholar’s reason for seeking the personal account will probably color the nature of the questions asked. In this case, the personal account will likely reflect the scholar’s interests more than those of the subject.

There are many motivations for the creation of personal accounts, including a focus on the self, on others, or on posterity. A narrator can offer perspectives on what he or she did, saw, or thought.2 These motives function to rationalize behavior, educate, and historicize. But these motives may not be immediately clear, and the reader may need to examine both the nature of the account and its contents to speculate about the reasons for its existence. A subject’s role in society is often a good indication of his or her motivations for composing a personal account. Does this subject have an agenda to defend or promote, such as a political position, social standing, or a place in the culture’s intellectual community?

An oral interview will be shaped by its format, context, and the particular circumstances of the session. Why is the interviewer interested in recording a particular personal account? That too will influence what is included or omitted. When the individual being studied is not living, the scholar must draw on historical sources for corroborative material to uncover conditions of the subject’s life that might not immediately be evident.

|

|

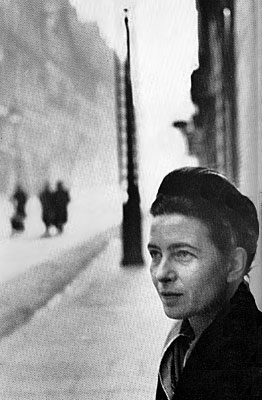

The existence of a personal account indicates a need on the

part of the subject to preserve his or her life story. Consider both the

stated and implied reasons for the creation of such an account, and the

value of the account as a representative voice in the culture. Was the

account easy to write, or did the writer take a risk? Simone de Beauvoir’s

memoirs reflect a great deal about women’s roles in Europe around

the period of World War II, but de Beauvoir was an intellectual who expected

to speak and be heard, to have her works published and debated. Contrast

her situation with that of Anne Frank, whose diaries were written in secret

while her life was in danger during the Holocaust. The two women experienced

a comparable historical period in very different ways, and their accounts

reflect such differences. One had time, access to materials, and an audience,

while the other had none of those. Yet each personal account is valid,

representing as it does an individual experience of the era.

|

Simone de Beauvoir

Anne Frank |