Designing for the History Web

Site Structure and Good URLs

t the same time that you are creating all of those lucid and perhaps even attractive web pages, you must also figure out where all of them will “go” when you’re finished, and how you will connect them. Although perhaps not as exciting as graphics and page layout, mapping a clear overall structure is critical to all well-designed websites. As Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville summarize in Information Architecture for the World Wide Web, such structure “clarifies the mission and vision for the site . . . and specifies how users will find information in the site by defining its organization, navigation, labeling, and searching systems.” Simply put, a properly structured site allows visitors to understand where they are, the location of the historical materials they want, and the site’s underlying logic, just as chapter divisions and subtitles help to organize a book. An online historical essay will have a very different structure than an archive, and an archive will have a very different structure than a website for a historical organization.30

t the same time that you are creating all of those lucid and perhaps even attractive web pages, you must also figure out where all of them will “go” when you’re finished, and how you will connect them. Although perhaps not as exciting as graphics and page layout, mapping a clear overall structure is critical to all well-designed websites. As Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville summarize in Information Architecture for the World Wide Web, such structure “clarifies the mission and vision for the site . . . and specifies how users will find information in the site by defining its organization, navigation, labeling, and searching systems.” Simply put, a properly structured site allows visitors to understand where they are, the location of the historical materials they want, and the site’s underlying logic, just as chapter divisions and subtitles help to organize a book. An online historical essay will have a very different structure than an archive, and an archive will have a very different structure than a website for a historical organization.30

Recalling from Chapter 2 that a website is fundamentally a set of files, web producers add structure by placing these files into “directories,” or distinct electronic folders on the web server, just as you place documents into specific folders on your personal computer. These directories become part of the URL of a web page, found between slashes to the right of a site’s domain name. The British Library has placed its digitization of the Magna Carta, for instance, at http://www.bl.uk/collections/treasures/magna.html, which nicely parses out to (reading from left to right), the web server of the British Library (in the U.K., of course), in their collections division directory, in the special “treasures” directory of the collections division (where the Magna Carta surely belongs), followed by the first word of the famous document and the “.html” that comes at the end of most web files. So that they will function properly on all types of computers, try to keep your directory and file names in lowercase, and eschew spaces or any symbols other than underscores and dashes.

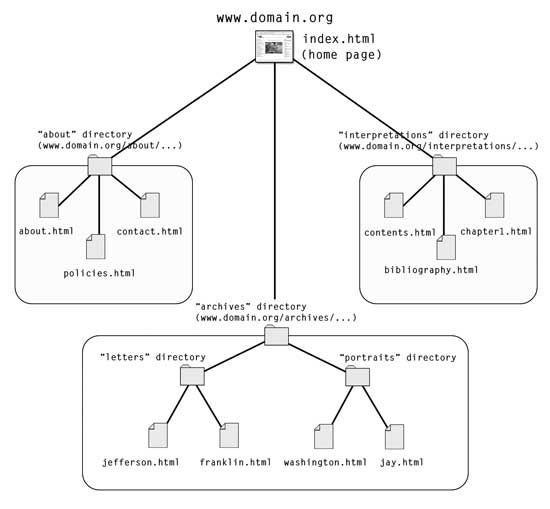

Creators of history websites should strive to emulate the clarity of the British Library’s site structure, using mostly words (where possible) rather than numbers or symbols for their directories, and naming directories in a sensible fashion that tells visitors—even without looking at the contents of the web page in the main window of the browser—where they are and what they can expect from a page. This process involves carefully grouping the materials you plan to put on your site. For example, a topical site might have some files that relate to teaching the subject matter, a set of interpretive essays, and a mass of raw archival documents. Although these materials could sit in a single directory, it makes sense both from the creator’s and the user’s perspective to divide the materials into three separate directories. Directories also can be nested, like babushka dolls, when a main section of a site has a set of subsections. Each URL slash indicates that the directory or file to the right of the slash resides inside of the directory named to the left of the slash. At the “top” of this hierarchy of directories and files, and providing an entrée to all of the others, is the home page, which is usually a file titled “index.html,” and to which the web server software automatically sends a visitor who types in your domain name. A diagram of a basic website’s structure can look like a genealogical tree, where a parent is a directory with children that are individual web pages.

Figure 32: A rough diagram of the major sections of yoru website and their contents will help you to organize your materials into “directories” of files on your web server, which will, in turn, help to clarify your site’s goals and structure for visitors.

Good sites sort themselves out and make their logical structure transparent through well-named directories and files. For instance, the African Studies Center at Boston University resides, aptly, at http://www.bu.edu/africa. Programs and courses underneath the umbrella of the center have their own directories, so the Environmental History of Africa course by James C. McCann can be found at http://www.bu.edu/africa/envr. This is a very easy URL to hand out to prospective students, though McCann did not have to skimp on the digital ink; http://www.bu.edu/africa/environmental would have been fine, too, and probably easier to remember.31 Beyond making it easier to hand out or email the clear URLs that it creates, good site structure allows search engines, particularly Google, to pick up on keywords in URLs and use them to assess how well a web page matches a search request (see Chapter 5).

Creating and displaying a lucid site structure is much easier for a simple history site like a small exhibit or a course website than for a complicated site like a museum collection with thousands of documents or artifacts. More complex websites such as large archives, as we noted in Chapter 2, tend to be database-driven and can have a relatively incomprehensible mix of letters and numbers following the domain name due to the way they pull information out of the database using a set of variables inelegantly appended to the URL. For example, JSTOR, the indispensable online journal repository, has especially ungainly URLs. Edd Wheeler’s article “The Battle of Hastings: Math, Myth and Melee” in Military Affairs, 52, No. 3 (July 1988), pp. 128–134, is found on the JSTOR site at http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0026-3931%28198807%2952%3A3%3C128%3ATBOHMM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-A, which is difficult to cite or type into a browser, much less remember. We would hope these URLs will not be truly “permanent” or “stable,” as they are so declared by JSTOR’s management. A more logical structure for JSTOR would highlight the key components of the site: the journal itself, then the year or volume number, then the number or month, then the pages or author. Modern web server software makes it possible to hide the numbers and variables for databases to produce more memorable URLs, though this feature is rarely used. Our suggestion for JSTOR, which has inadvertently out-Deweyed the Dewey Decimal System, would be to recast poor Edd Wheeler’s online article as http://links.jstor.org/military_affairs/52/3/128-134.html, or better yet http://links.jstor.org/military_affairs/1988/june/wheeler.html. Note how easy it would be to go straight to another article under this revised system; if you knew the journal name, date, and author, you could type them directly into the location box in your browser without having to page through search results or tables of contents.32

The importance of comprehensible web addresses should caution historians against using frames on their sites because these HTML elements generally mask a site’s true URLs and thus its structure. (Frames, or the ability to split a web page into separately functioning windows, are a poor idea in general because they tend to breed confusion, e.g., when you click on a link to another site in one window and remnants of the initial site stubbornly remain, hogging part of the screen and making it unclear which site you are on.) For example, though attractive, the Koninklijke Bibliotheek’s Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts website suffers from a major flaw. How do you bookmark a specific folio, or more important, cite one of the remarkable folios the National Library of the Netherlands has spent the time and money to digitize? Unless you are a technically savvy user, all you get when you try to bookmark or cite a folio is the URL for the overall directory because the image of the folio resides in a secondary frame. This lack of specificity may upset scholars more than the general browsing public, but it shows how reliant—perhaps unconsciously—we are on good site structure and useful URLs.33

30 Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville, Information Architecture for the World Wide Web (Cambridge, Mass.: O’Reilly, 1998), 10; Aaron West, “The Art of Information Architecture,” iBoost Journal, ↪link 4.30.

31 Note the lack of “.html” here—most web servers will automatically look for the file “index.html” or “home.html” in a folder or directory, which means that for home pages you can just use a short form of the URL if you name it one of those options. In other words, the full URL for McCann’s site is actually http://www.bu.edu/africa/envr/index.html, but the abridged form is perfectly acceptable.

32 These plainer URLs can be created using some technical capabilities that most web server software programs have, such as mod_rewrite for the most popular web server software, Apache. In general, try to avoid query strings, those ungainly strings of numbers and symbols after the question mark in a URL. The History Cooperative uses an addressing system of the sort we advocate. For example, Kenneth Cmiel’s essay on “The Recent History of Human Rights” in volume 109, issue number 1 of the American Historical Review is found at http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/109.1/cmiel.html.

33 Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, ↪link 4.33.