Owning the Past? The Digital Historian’s Guide to Copyright and Intellectual Property

Protecting Your Intellectual Property

or an entirely different set of reasons, we don’t think historians should spend much time agonizing about how to protect their own intellectual property rights. Recent laws and court decisions have significantly increased the protection for creators of intellectual property. You do not have to do anything to make yourself eligible for the protection of the copyright law. Contrary to popular belief, you no longer (since 1989) need to place a copyright notice on your work.20

or an entirely different set of reasons, we don’t think historians should spend much time agonizing about how to protect their own intellectual property rights. Recent laws and court decisions have significantly increased the protection for creators of intellectual property. You do not have to do anything to make yourself eligible for the protection of the copyright law. Contrary to popular belief, you no longer (since 1989) need to place a copyright notice on your work.20

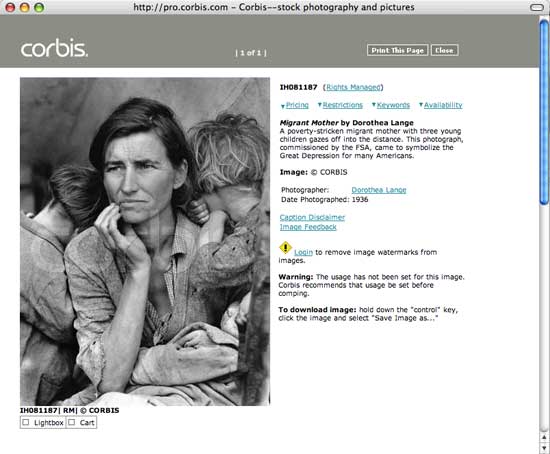

If so, why does anyone bother? Well, for one thing, placing a copyright notification on your website isn’t much bother. You simply write “ © Charles Beard 2003” on the bottom of your home page. (If you can’t get your software to create the symbol, you could write “Copyright” or “Copr.” but not “(c)”.) And for this minimal effort, you remind readers that you care about the rights to your intellectual property.21 We recommend including a copyright notice but not one of those overly broad warnings that proclaims, “no part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without express permission.” Such notices go well beyond the copyright law, offer no additional protection, and implicitly challenge the doctrine of “fair use” that digital historians should cherish. Good copyright citizens—cooperative residents of the digital commons—don’t try to grab rights they don’t have. (Some, as we will discuss, even avoid claiming all of the rights to which they are entitled.) Bill Gates’s online digital image repository, Corbis, includes copyright notices on thousands of public domain images. “These claims,” says attorney Stephen Fishman, “are probably spurious where the digital copy is an exact or ‘slavish’ copy of the original photo.” Some websites even slap copyright notices on famous public domain texts. At the bottom of a copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, the Atlantic Monthly website adds the following: “Copyright © 1999 by The Atlantic Monthly Company. All rights reserved.”22

Figure 41: Corbis, a commercial digital image repository, puts copyright notices (and digital watermarks) on thousands of public domain images such as dorothea lange’s famous Migrant Mother photo, which was taken as part of the government-sponsored FSA photography project and is available for free through the Library of Congress website.

Even the most carefully placed or most threateningly worded copyright notice does not protect you if the work does not meet the requirement enunciated in the Feist case that copyrightable works reflect a minimal degree of creativity and originality. You can spend thousands of hours scanning and digitizing public domain documents—say, the entire New York Times from 1865 or all of Charles Dickens’s novels—but, according to most lawyers, you can’t copyright the results. Even if you modernize the typeface, correct the spelling errors, and reformat the spacing in a nineteenth-century novel, you have not met the law’s standard of minimal creativity. The same—Corbis’s copyright notices to the contrary—applies to scanned images of public domain photos. And it equally applies to the massive online historical databases—including the fifty million records in the Church of Latter-day Saints online compilation of the 1880 U.S. Census. Some of the most time-consuming work that digital historians are currently undertaking is not covered under copyright law. But we hope that other good citizens of the digital commons will respect and credit your labor even while they take advantage of the court’s decision allowing them to make active and free use of it.23

If your work is, in fact, eligible for copyright, registering it (as well as placing a notice) makes it easier for people to find you (not usually an issue for online works) and gives you additional protection. You can’t, in fact, sue anyone in federal court for violating your copyright unless you first register. You can, however, simply wait and register only if it becomes necessary. But if you wait, you can’t recover as much in a suit. Only if you register your work within ninety days of publication are you entitled to “statutory damages” and attorney fees rather than just actual damages. Statutory damages send a sharp message against infringement and can greatly exceed the financial harm suffered. Ocean Atlantic Textile Screen Printing found that out when it produced 2,500 t-shirts adorned with a copyrighted photograph by Ruth Orkin. They made only $1,900 from the shirts, but Orkin’s daughter won $20,000 in statutory damages and $3,000 in attorney fees. Even more dramatic is the case of UMG Recordings v. MP3.com, in which the major recording companies won $25,000 per CD uploaded on the MP3.com system in statutory damages. Potential damages could run as high as $250 million.24

Of course, few historians have much prospect of collecting millions in statutory damages for violations of the copyright of their website. You should weigh the potential gains of a lawsuit against the time and expense in registering your website with the copyright office. Indeed, you may be surprised to learn that it is even possible to register a website. The cost is modest ($30), but the actual copyright deposit is complicated because the office acknowledges that, as yet, “the deposit regulations of the Copyright Office do not specifically address works transmitted online.” In the meantime, they will accept computer disks or printouts—neither of which is easy to produce for a major website.25 We recommend that until the Copyright Office simplifies the registration procedure (and perhaps not even then), you shouldn’t waste your time registering your site.

In any case, most historians worry more about someone stealing their work for credit rather than for money. Historians considering putting their work online commonly express the anxiety that “someone will steal it.” They fret more about the sin of plagiarism than the crime of copyright infringement. And plagiarism and copyright infringement are very different matters; Stephen Ambrose, who copied only short passages of text, could probably plead “fair use,” even if we would not think of his use as “fair” in the moral sense we associate with eschewing plagiarism. To be sure, someone is more likely to steal your work if it is on the web than if it is in your desk drawer. But placing your work on the web actually gives you a better way of establishing that you are the original author than would be true of a paper that was delivered only orally at a conference. Moreover, historians are often most concerned about someone stealing their ideas, and the copyright law does nothing to protect ideas, only their formal and fixed expression. The most important goal for historians should be the circulation of ideas and expressions, and the web offers a wonderful new tool for such dissemination. We should focus more on getting others to pay attention to what we have to say rather than on ensuring that the proper individual gets the proper credit.

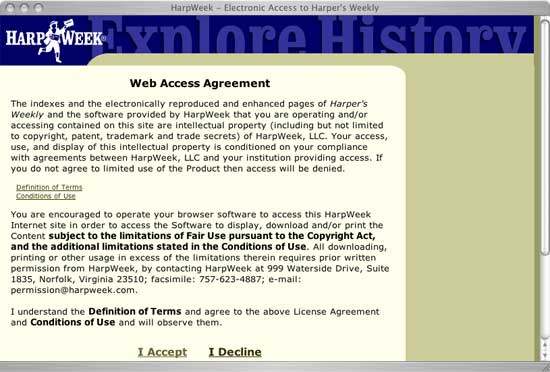

If you remain paranoid about wide and anonymous access to your work on the open web, you can restrict access through passwords or by Internet Protocol (IP) addresses (the unique numbers by which Internet connected machines are identified, the security approach used by many commercial and some nonprofit websites). A related form of noncopyright restriction is a license, which asks users to agree (in effect, contractually) to some conditions on their use of a website. These licenses have proliferated in recent years—in part as a response to the lack of copyright protection for electronic databases and more generally because, as librarian Mary Case points out, publishers believe they will be more successful in suing for breach of contract than copyright infringement. Such licenses can even try to restrict your use of public domain material. For example, HarpWeek presents public domain material from Harper’s Weekly, but the license imposed on subscribers still limits access to and use of the site’s content. Some attorneys question, however, whether licenses restricting access to public domain materials are legally enforceable.26 Some historians—including the authors of this book—question whether such restrictions are in keeping with the original, open spirit of the web.

Figure 42: HarpWeek presents public domain material from the nineteenth-century periodical Harper’s Weekly. But it asks users to click a button to signify their assent to “conditions of use” that restrict one’s ability to use the material freely.

Our discussion here about your rights and responsibilities conceals a crucial ambiguity for many readers of this book. After all, digital history tends to be much more collaborative than traditional historical scholarship. You need to figure out upfront how to recognize adequately everyone’s contributions—including those of students and volunteers—or risk facing later wrangles that can be much more unpleasant than disputes over copyright. In addition, many historians work for an institution rather than themselves. Museum curators, librarians, and archivists who create websites know that under the “work for hire” doctrine, their employers own the copyright to their creations.

But what about college instructors? For much of the twentieth century, academics have operated under the “teacher exception,” which says that instructors and not their employers own the intellectual fruits of their labor. But many lawyers see the 1976 Copyright Law as marking the demise of the teacher exception. At the moment, however, most university policies accept the spirit, if not the letter, of the teacher exception, at least for traditional academic writing. But those who are concerned about this issue need to follow historian-turned-lawyer Elizabeth Townsend’s advice to “Read All employer IP intellectual property policies carefully.” This is doubly true for those producing course materials and websites, which Townsend describes as “an area in flux.” Universities are more likely to claim ownership of websites, especially course websites, created with significant university resources such as the help of research assistants and instructional resources offices.27

Others, however, argue that scholars shouldn’t bother worrying about property rights in their work. Corynne McSherry, another academic-turned-lawyer, wonders whether academic work should be owned at all and argues that scholars should instead maintain their realm as a world of gift exchange, in which ideas circulate freely, rather than a world of commodities that are bought and sold. She argues that the very effort to maintain the teacher exception may be self-subverting. When teachers aggressively insist on intellectual property rights to course materials, they foster the idea that courses are just another commodity and instructors are just another kind of worker, which undercuts the basis of the “teacher exception” in the “idea that professors are special—that they’re not like other kinds of knowledge workers.”28

For those like McSherry, who view academic work as a matter of sharing, copyright law is more of a hindrance to the free circulation of historical ideas, interpretations, and sources. Those in this camp also see the insistence on property rights as conflicting with the ethos of sharing and cooperation that has been an attractive feature of the web and is embodied in the open source and free software movements, which generally oppose the private ownership of software. Much of this software (like the operating system Linux and the software Apache, MySQL, and PHP, which run much of the Internet) has been released under the “General Public License” (GPL) or a license compatible with the GPL, which was developed by free software activist Richard Stallman to ensure that software licensed under it—and any derivatives—remain permanently in the public domain.29

Some have tried to take the ideas behind the GPL and open source and apply them to other forms of expression—for example, to the words of historians rather than the code of programmers. One effort, called Creative Commons, is “trying to transfer some of the lessons from … open source and free software to the content world,” in the words of executive director Glenn Otis Brown. “Copyright is about balance,” he observes. “We hope Creative Commons . . . helps put copyright balance back in vogue.”30

So far, Creative Commons has primarily encouraged copyright balance by offering free legal advice to those who want to promote an ethic of sharing and mutuality. With the help of some high-priced legal talent, they have developed a series of licenses packaged under the rubric “Some Rights Reserved.” For example, their “noncommercial license” permits free use and distribution of work only for noncommercial purposes. Other historians, who put a priority on getting their perspectives widely disseminated, might select the “attribution” license, which allows any site to display their work if it gives them credit. If you are even more firmly committed to the free circulation of historical work, you might simply deposit your work into the public domain with no strings attached. Short of this more drastic step, you might find the “Founders’ Copyright” option appealing—especially because it has the particularly historical twist of mimicking the arrangements established in the 1790 copyright law and guaranteeing the entry of your work into the public domain after fourteen years (or twenty-eight years if you choose to renew the copyright once).31 Copyright radicalism in the early twenty-first century has come to mean embracing an eighteenth-century law.

20 United States Copyright Office, Circular 1: Copyright Basics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Copyright Office, 2000), ↪link 7.20. At least as far back as 1909, copyright registration has not been a condition of protection. See Washingtonian Publishing Co. v. Pearson, 306 U.S. 30, 36 (1939). The one exception was that if the Registrar of Copyright asked you to register (in connection with copyright deposit) and you refused, you could also lose your rights. The 1976 law liberalized notice requirements (starting in 1978), but they remained in effect until 1989.

21 According to Peter Vankevich of the Copyright Office, only putting the copyright notice on your home page is roughly analogous to the standard practice of only putting a copyright notice at the front of a book. But though only posting a notice on your home page is sufficient, he believes it is a good idea to put the notice on every page of your site. Peter M. Vankevich, interview, 24 November 2003.

22 Fishman, The Public Domain, 17/11, 14 and 6/10. See also Regents Guide. On Corbis, see Kathleen Butler, “The Originality Requirement: Preventing the Copy Photography End-Run Around the Public Domain” (paper presented at the NINCH Copyright Town Meeting: The Public Domain: Implied, Inferred and In Fact, San Francisco, 5 April 2000), ↪link 7.22a, which challenges the Corbis claims of copyright and the contrary position at the same NINCH town meeting presented by Dave Green of the Corbis legal department. “NINCH Copyright Town Meeting: The Public Domain: Implied, Inferred and In Fact, San Francisco, 5 April 2000,” NINCH, Meeting Report, 2000, ↪link 7.22b. Kathleen Butler, “Keeping the World Safe from Naked-Chicks-in-Art Refrigerator Magnets: The Plot to Control Art Images in the Public Domain Through Copyrights in Photographic and Digital Reproductions,” Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal 21 (Fall 1998), 55–128. There are ethical and legal issues involved in taking digital copies of public domain documents that others have posted on the web. The legal issues involve whether they have made significant editorial changes that would entitle them to copyright. The ethical issues involve the credit that someone deserves for the “sweat of brow” in scanning the documents. For a long debate on this, see E-DOCS: Exchanges Among Jon Roland,Paul Halsall, and Jerome Arkenberg ↪link 7.22c.

23 Fishman, The Public Domain, 17/10–11. Some significant enhancements of the original data might be entitled to protection; let’s say you provided annotations explaining the occupations listed in the census records. The proposed “Database and Collections of Information Misappropriation Act (HR 3261),” which is being advocated by large information conglomerates like Reed Elsevier, could change this situation by making the facts assembled in a database eligible for copyright-like protection and making it illegal to make commercially available “quantitatively substantial” portions of a database, although it could be subject to constitutional challenge if passed. See Lisa Vaas, “Putting a Stop to Database Piracy,” eWeek (24 September 2003), ↪link 7.23a; “Your Right to Get the Facts Is at Stake,” Public Knowledge, ↪link 7.23b; Sebastian Rupley, “Critics Assail Proposed Database Law,” PC Magazine (3 March 2004), ↪link 7.23c. Note that “database” is an expansive concept, which includes websites themselves, as computer programmer David Brooks found out when another site—legally—appropriated much of his site on Vincent Van Gogh. Nancy Matsumoto, “When the Art’s Public, Is the Site Fair Game?” New York Times, 17 May 2001, G6; Blanke, “Vincent Van Gogh, ‘Sweat of the Brow,’ and Database Protection.”

24 Circular 1: Copyright Basics; Engel v. Wild Oats, Inc., 644 F. Supp. 1089 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 3, 1986), ↪link 7.24a; Michael Landau, “‘Statutory Damages’ in Copyright Law and the MP3.com Case,” GigaLaw.com, ↪link 7.24b. Statutory damages currently range from $750 to $30,000 per work infringed, with a maximum of $150,000 per work for willful infringement.

25 U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 66: Copyright Registration for Online Works (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Copyright Office, 2002), ↪link 7.25a. The case for registering is made at “Copyright Registration: Why Register?” Copyright Website ↪link 7.25b. This is not unbiased, however, in its encouragements to register because the site offers to register your website for you for $99. According to Vankevich, the U.S. Copyright Office regularly receives several thousand applications each year to copyright websites. It has not decided how to respond to the constantly changing content inherent to the medium. Vankevich, interview.

26 Fishman, The Copyright Handbook, 2/11, 14/14, 17/15; Mary Case in “NINCH Copyright Town Meeting: The Changing Research and Collections Environment: The Information Commons Today, St. Louis, March 23, 2002,” NINCH, Meeting Report, 2002, ↪link 7.26a. For example, HarpWeek requires you to consent to a “web access agreement,” which says you will not “store the downloaded Content in any electronic/magnetic/optical or other format now known or hereinafter created for more than ninety (90) days.” Although some question the enforceability of such licenses, they are valid in Virginia and Maryland, which have passed the Uniform Computer Information Transactions Act (UCITA) giving priority to licensing over copyright. See, for example, “NINCH Copyright Town Meeting: Copyright Perspectives, Rice University, Houston, April 25, 2001,” NINCH, Meeting Report, 2001, ↪link 7.26b. On UCITA, see “UCITA,” American Library Association, ↪link 7.26c. Peter Jaszi describes efforts to protect databases through licenses as “quasi-copyright.” Herman, “Roundtable,” 39.

27 Townsend writes “the growing trend is to see the ‘teacher exception’ as created not by judge-made law its previous basis but by individual university policies.” In other words, whether or not your work as a teacher is considered “work for hire” depends on what your employer says. Elizabeth Townsend, “Legal and Policy Responses to the Disappearing ‘Teacher Exception,’ or Copyright Ownership in the 21st Century University,” Minnesota Intellectual Property Review 2.3 (2003): 210, 272, 277, 279–80, ↪link 7.27. Recent cases suggest the persistence of the exception for “books and articles,” although textbooks based on course materials could be an ambiguous case. The “teacher exception” apparently does not exist within the European Union.

28 Corynne McSherry, Who Owns Academic Work? Battling for Control of Intellectual Property (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001); Jeffrey Young, “Law Student Warns That Professors’ Quest for Rights to Lectures Could Backfire,” Chronicle of Higher Education (6 November 2001), ↪link 7.28. Townsend’s article offers a sharp rejoinder to McSherry, whom she sees as discouraging “academics and from using the law and court systems to protect their work, demonizing those who do and accusing them of changing the tone of the university into a space fearing litigation.” Townsend, “Legal and Policy Responses to the Disappearing ‘Teacher Exception,’” 209.

29 “GNU General Public License,” GNU Operating System—Free Software Foundation, ↪link 7.29.

30 D. C. Denison, “For Creators, An Argument for Alienable Rights,” Boston Globe, 22 December 2002, E2; Kendra Mayfield, “Making Copy Right for All,” Wired News (17 May 2002), ↪link 7.30.