|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

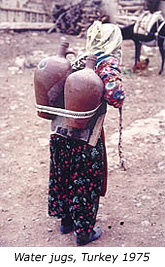

A stone cylinder by itself may not mean much, but one found along with a flat stone and grains of wheat may suggest purpose, such as grinding grain. Museum exhibits often present information, including photographs, on an object's discovery and related objects. Exhibits may include sketches that “fill in” missing parts or illustrate how an object likely was used. The ethnographic museum in Istanbul, Turkey, shows nomads in a tent, demonstrating daily use of everyday objects such as rugs. Similarly, Istanbul's Topkapi Saray museum, housed in the sultan's palace, uses costumed mannequins to show how women in the harem lived.

To use objects for research, start by asking how and where they were found. Where are they now? How are they presented? This information can be rich and layered. For example, the inlaid metal tray you use as a coffee table may have been purchased by your grandmother from a craftsman who made it in Damascus, Syria, 60 years ago. A gold coin with an image of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I may have been found in a 6th-century Chinese tomb. Each object has a story. Your grandmother's tray may tell about her enthusiasm for travel or her taste, but little about the history of Damascus. The Byzantine coin found in China may provide vital evidence about trade or other contact between East and West and may provide new insights into Chinese burial rituals.

Many objects used to understand the past were uncovered by archaeologists. Only in the late 19th century, however, did archaeologists begin to record exact object locations—not a town or a site but the exact place within the site and in reference to other objects. The relative positions of objects often allow for the most meaningful interpretation. Archaeologists try to understand what objects are grouped together and what appears in the same chronological layer. An undatable object may be dated by its proximity to other objects whose dates are known. The layers in an archaeological site begin with the earliest at the bottom and the most recent near the surface. Yet when archaeologists remove objects, they destroy the sites, leaving only their record and the objects.

How can you begin to answer such questions about an object? Start by gathering as much information as possible. Are there identifying marks on the object—a date, a location, the creator's name, inscribed words? If there are such marks, can you tell what language they are written in? If all you have to work with is a picture, when was that picture created and by whom? You may end up with more questions than answers, but this important first step may lead you to the answers you seek. | ||||||||||

|

finding world history | unpacking evidence | analyzing documents | teaching sources | about |

||

The biography of the object includes information on owners of the object over an extended period of time and may reveal how the object was used or perceived in different settings, perhaps in ways unintended by its creator. An object produced for a practical function in daily life may acquire symbolic value at a later time. Or an object's original function may become irrelevant because society no longer has use for it or because people no longer know how the object was originally used. Most objects have passed through several historical stages and the location of discovery is rarely the site of production. How did the object reach its location of discovery? What does the context tell us about the object's environment and associations? Does the context provide information about date? Such evidence may reveal patterns of exchange and interaction.

The biography of the object includes information on owners of the object over an extended period of time and may reveal how the object was used or perceived in different settings, perhaps in ways unintended by its creator. An object produced for a practical function in daily life may acquire symbolic value at a later time. Or an object's original function may become irrelevant because society no longer has use for it or because people no longer know how the object was originally used. Most objects have passed through several historical stages and the location of discovery is rarely the site of production. How did the object reach its location of discovery? What does the context tell us about the object's environment and associations? Does the context provide information about date? Such evidence may reveal patterns of exchange and interaction.