Building an Audience

Tracking and Assessing Your Audience

espite the high technology of the web, it can be surprisingly hard to know whether your site is reaching its intended audience and achieving its overall goals. Speculating about a website’s audience can be similar to the fable of the six blind men who came to wildly different conclusions about an elephant they encountered, based solely on the part they touched. Nevertheless, some tools and techniques can help you better know your audience. Every time someone

visits your server (or the server that houses your site), they leave a series of electronic traces that the computer might record cryptically as follows:

espite the high technology of the web, it can be surprisingly hard to know whether your site is reaching its intended audience and achieving its overall goals. Speculating about a website’s audience can be similar to the fable of the six blind men who came to wildly different conclusions about an elephant they encountered, based solely on the part they touched. Nevertheless, some tools and techniques can help you better know your audience. Every time someone

visits your server (or the server that houses your site), they leave a series of electronic traces that the computer might record cryptically as follows:

81.174.188.105 - - [02/Jun/2004:04:59:35

-0400] “GET /d/5148/ HTTP/1.1” 200 4905

“http://www.google.com/search?q=AIR+RAID+WARDEN&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8”

“Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; PPC Mac OS X; en-us) AppleWebKit/125.2 (KHTML, like

Gecko) Safari/125.7Put into English, this “sentence” tells us that on June 2, 2004, at 4:59 A.M. Eastern Daylight Time, a computer connected to “Force 9,” an Internet service provider in Sheffield, England (where it was a more sensible 9:59 A.M.) that owns the IP address 81.174.188.105, sent a request to CHNM’s web server on the George Mason University campus for a web page that contains the words to the 1942 tune “Obey Your Air Raid Warden,” a big band recording that doubled as a wartime public service announcement. (We know this because these are the logs for our Historymatters server, and the machine has requested—with a “get” command—the page http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5148.) The Google search engine kindly referred our British visitor after he or she entered the words “air raid warden”—a search for which Google ranks us first. Back in England, our visitor read our page on a Macintosh computer with the Mac OS X operating system (update 10.3.4) and the Safari browser.19

The server faithfully records each one of these connections and saves them into files, called “logs,” that can run into millions of lines. None of us has the time to read through these massive logs, and so fortunately programmers have written log analysis software (with names like NetTracker, Absolute Log Analyzer, Web Trends, and Webalizer) that summarize them in easier to read charts and graphs. If you don’t run your own server, you will be limited to the program your provider uses.20

Log analysis programs compile pages and pages of “hard” numbers about your visitors. But they turn out be squishy soft when you press on them. The most misleading and misused statistic—although one still frequently cited—is “hits.” You will often hear people boasting about the millions of hits their site gets (and we must admit we have ourselves indulged in this conceit). But the number is largely meaningless. Hits merely count each one of the lines from the log files. If, however, you read further in the log file quoted above, you will see seven lines (hits) from our English visitor—most of them recording that his or her computer requested six different images embedded in a single web page. Thus, if we added two more graphics to that page, our number of hits would suddenly jump by almost one-third. Bad design—having too many images on your pages—would allow you to brag about more “traffic.”21

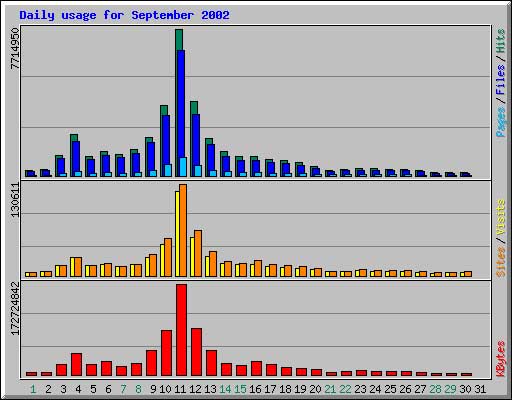

Figure 33: Raw numbers of hits and visits in web logs can be misleading, but they do clearly indicate trends in usage. Here, we see the huge jump in visits to the September 11 Digital Archive on the first anniversary of the attacks.

Because most people really want to know about “visitors” rather than “hits,” log analysis programs offer that statistic and it appears to be more reassuringly solid—a measure of how many people come to your site. But the problem is deciding what constitutes a “person” when we only know about one machine contacting another machine. Our English visitor departed after looking at the lyrics to “Obey Your Air Raid Warden” and appears no further in our logs for the next twenty-four hours. It seems easy to describe him/her as a single “visitor” to our site. But what about the person from 203.135.21.42, who shows up in the logs at 5:52 a.m. and is still looking around at 6:03a.m. after stops at various different pages. Was that a single visitor? Probably. But what if 203.135.21.42 is the IP address of a computer in a university computer lab? A student comes in and takes a look at our site and then leaves. Five minutes later another student arrives and sits down at the same machine and also visits—perhaps they both have the same assignment. How do we know if that was really two “visitors” or whether it was simply the first student who had been interrupted by a friend and then returned to looking at the site? From the perspective of the server, they are the same—two requests from the same machine across the Internet.

Further complications arise because people can simultaneously (rather than sequentially as above) access your site from the same IP address. That is the case with many AOL users who are directed around the Internet from massive “proxy servers” (intermediate computers that group many web surfers under one IP address), or with some student labs (especially in high schools) that are behind a firewall and proxy server for reasons of security or student control. Thus fifty students from a class could access your site in an hour, but they would all appear to come from the same IP address. Another problem posed by Internet service providers like AOL is that its servers “cache” (save a copy of) frequently requested pages, which means their readers don’t show up in the logs at all.22

To decide on your number of visitors, the log analysis program therefore makes a guess that any series of requests from a single IP address during a preset period (generally thirty minutes) counts as one “visitor.” That can mean that it is under-counting your traffic, as in the example above, or over-counting it as when a single person spends two hours on your site and is counted as “four visitors.” It is even more misleading to confuse “visitors” with “users.” After all, a single person who quickly stops at your site three times a day would count for more than 1,000 of your annual visitors. (That person may very well be you, obsessively checking on your site.) And keep in mind that not all of these “visitors” are living, breathing people. A request to your machine from an automated program—most commonly a “bot” operated by a search engine company—counts just as much as one from a high school student in Iowa, unless you set your analysis program to exclude such visitors from its calculations.

The final aggregate statistic from logs—page views (a count of requests to load a single web page)—has the virtue of not being a statistical construct. Page views measure how many actual pages from your website your server has sent out—in effect, it counts “hits” without the graphics. Perhaps because it is less subject to manipulation, this figure has emerged as the most frequently cited number by websites. Even so, you can easily break your content into shorter “pages” and thereby up your page view count.

In any case, you should avoid confusing either “visitors” or “page views” with the active use of your site. After all, many web visitors depart with barely a glance at your pages, as with our English friend who was probably hoping to learn something about English, rather than American, air raid wardens. Commercial sites cast an even more skeptical eye on such statistics. One new media commentator points out that “traffic by itself is actually a burden” because it makes your website slower and less reliable, requires extra customer service and technical support, increases your web hosting charges, and “distracts you from your key goals.” “Page views without corresponding sales,” observes Marketingterms.com, “may even be viewed as an expense.”23 (Of course, if you are selling advertising, then page views are precisely what you want to deliver.) You should try much harder to measure active users of your site—for example, by noting how many people write in your guestbook, ask to be added to your mailing list, or download files—than to count passive visitors.24

In the commercial world, no one trusts the self-reporting of hits, visitors, and page views. Instead, Nielsen/NetRatings (the same folks who bring you TV ratings) and comScore Media Metrix track web usage from a representative sample of users through monitoring devices installed on their computers. News reports that Yahoo, Microsoft, and Google are the most visited websites come from summaries these services provide. (The detailed reports, which offer demographic breakdowns sought by advertisers, circulate only to those who pay for high-priced subscriptions.) Although the sample sizes are vastly larger than for television (more than 100,000 for Nielsen and 1.5 million for comScore), the monitoring challenge is also much greater. Even with cable, TV viewers have only dozens of choices; web surfers can choose from millions of sites. In addition, TV ratings services can just focus on folks gathered before the home television hearth, but the web ratings services need to consider the vast amount of surfing done during the workday. As a result, the two rating services often report divergent numbers, and advertisers (the main audience for these studies) gnash their teeth in frustration over the “discrepancies and inconsistency” in the data.25

In the end, self-reported log numbers are largely about PR, about making your funders and supporters feel good about your efforts—hence, the temptation to brag about millions of hits rather than tens of thousands of visitors or the failure to report less edifying statistics such as the number of people who leave your site almost immediately. For the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation, for example, a listing of the visitors and hits at www.ellisisland.org occupies a parallel place in their Annual Report to physical visitors to Ellis Island and number of employees on the payroll.26

The more important use of logs is the internal analysis that you can do to help you understand how your site is being used and by whom. Unfortunately this can be a very time-consuming process. But here is a list of some of the information provided by a typical log program and how you might use it:

Requested Pagestells you about your most popular pages, an essential tool for gauging what your audience wants. Angela O’Neal, the project manager for Ohio Memory, notes that they look at these figures to help them plan what projects they might do next. Harry Butowksy, the webmaster for the National Park Service, says that they sometimes move content with a lot of hits to a more prominent location on the site to make it easier to find.27 Some related statistics—traffic by pages, entry pages, and requested downloads—provide similar clues as to what is popular on your site. By contrast, “exit pages” can sometimes offer hints about pages that are not keeping visitors within your site. Analysis programs can generally tell you which pages prove the “stickiest,” the ones that visitors linger over the longest. But be prepared to be depressed by the large number of visitors who depart from your site in less than one minute.

Referrers tells you about the sites that are providing important links as well as the search engines that drive traffic to your site. Such information helps to give you a better sense of your audience, what they are seeking on your site, and the kinds of relationships you should cultivate (and the kinds of materials you should provide) to increase your audience. A log analysis program can tell you what words and phrases people are most often entering into Google and then being directed to your site. For example, “Atlanta Compromise” is a popular search term that brings people to History Matters—probably because we include an audio clip from Booker T. Washington’s famous “Atlanta Compromise” address of 1895. Knowing that might lead us to expand our coverage of the address and Washington.

Browsers and Operating Systems: As you have learned in Chapter 4, getting your pages to display properly on multiple platforms and browsers can be frustrating. But if it turns out that only 0.3% of your visitors are browsing with Netscape Navigator 4.0, you should not devote major resources to getting your site to work well with it.

Traffic Patterns: Log software can give you nicely arranged graphs of traffic at your site by the hour of the day and by day of the week. Commercial sites—concerned about bursts of traffic, interested in monitoring sales promotions, or staffing their shipping department—find this information enormously useful. But it can still help you to gauge some of your own promotional efforts. For example, Rick Shenkman, who emails his HNN newsletters on Wednesday and Friday, can tell that the Wednesday edition brings more traffic to the site.

Despite their limits, logs can provide a revealing window into how your site is being used. But serious analysis takes considerable time. Major commercial websites such as Discovery.com have research staffs that issue weekly reports on the traffic logs. For those of us who don’t do this for a living, it is hard to carve out the time to study logs, but it is something you should examine quickly on a regular basis and more closely at least every six months. A very active history site like Colonial Williamsburg reviews log reports monthly.28

Still, even the most sophisticated log analysis will only tell you about aggregates and patterns rather than individuals. If you want to know how particular individuals use your site, you need to ask them first to register with you. If they are registered on your site, you can track their usage with “cookies”—small text files placed on their hard drive by your website’s server. Usually this file contains a simple ID number, which allows the website page in question to know that you’ve visited there before. Cookies allow Amazon.com to greet you by name when you arrive on their site. Cookies would allow you to customize your home page for different visitors or to remember what photograph they were studying or which multimedia player they use to play streaming audio. But that requires some technical expertise and also runs the risk of alienating those who view these “foreign objects” with suspicion. We would advise you to think carefully before programming your website to place cookies on visitors’ computers.29 Providing respected and frequently used historical resources online involves cultivating trust, and hidden technologies like cookies—however innocent—can be counterproductive in an age of spam, viruses, and spyware.

A more open approach to learning about your audience is to seek out their views directly. As we have noted, mandatory registration can drive away visitors, but a voluntary guestbook that gathers names and addresses is generally a good idea. Even if you don’t plan on issuing a newsletter, a mailing list of regular site users is invaluable. If you are planning an overhaul of your site, you can write and ask for feedback. If you are applying for grants, it could be the source of helpful letters of support. Surely the best way to learn about your audience is by talking to them in person, either one on one or in “focus groups.” Arranging commercial focus groups is an expensive proposition, but historians with captive audiences of students or museum visitors can do this relatively inexpensively. Bruce Tognazzini, one of the creators of the Macintosh interface, encourages all creators of electronic designs to convene less formal focus groups (however unscientific) for helpful feedback.30 In these settings, you get the richest information on what users find most and least useful, and most and least confusing or off-putting, about your site. Angela O’Neal notes that staff from Ohio Memory tries to meet with users at least once a year to ask them how they would like to see things evolve or change. She describes this as “the most helpful tactic,” much more useful than studying server logs.31

This connection to “real” people is important not simply because face-to-face interactions offer rich and dense responses that are hard to capture online, but also because it breaks down the illusion that online communities are somehow fundamentally different and separate from those that exist offline. “The hidden assumption,” observes Phil Agre, “is that the ‘community’ is bounded by the Internet. But communities are analytically prior to the technologies that mediate them. People are joined into a community by a common interest or ideology, by a network of social ties, by a shared fate—by something that makes them want to associate with one another.” You will be most successful as a history website operator if you understand that your goal is not to attract anonymous (and often meaningless) hits on your server but rather to “support the collective life of a community.”32 Chapter 6 describes another way to do that—by not just presenting the past but also by collecting it, by not just talking to your audience but also by listening to them and making their voices part of the historical record.

19 For a good overview of logs, see Michael Calore, “Log File Lowdown,” WebMonkey, ↪link 5.19.

20 As with most other things, you can outsource your log analysis to a service provider, which installs some programming code on your web pages and then provides continuously updated reports online. Such services can run $100,000 to $250,000 per year—well beyond the budget of a typical nonprofit history site. Jim Rapoza, “Vital Web Stats—And More,” eWeek (26 August 2002), ↪link 5.20a; “Web Log Analyzers,” GlobalSecurity.Org, ↪link 5.20b.

21 If you redesign your site, your hits can decrease while your number of visitors increases, as seems to be the case for the American Family Immigration History Center, which saw its hits drop from 3.4 billion to 2.5 billion while its visitors grew from 1.7 to 2.4 million. Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Annual Report, Year Ended March 31, 2003 (New York, 2003), 5.

22 Robin Good, “Monitoring Your Web Traffic Online—Part II Log Analysis Tools,” Master Mind Explorer (31 August 2001), ↪link 5.22a; You can control how your site is cached by AOL, however: “AOL Caching Info,” AOL.Webmaster.Info,↪link 5.22b; “AOL Proxy Info,” AOL.Webmaster.Info↪link 5.22c.

23 Jon Weisman, “Not All Page Views Are Created Equal,” E-Commerce Times (4 October 2002), ↪link 5.23a; ↪link 5.23b.

24 Shannon, Building an Effective Website, 27.

25 Kate Fitzgerald, “Debate Grows Over Net Data; NetRatings, ComScore Numbers Diverge,” Advertising Age (15 March 2004). See also “Can We Get an Accurate Accounting of Website Visitors?” DSstar 4.38 (19 September 2000), ↪link 5.25a. Another system of ranking is offered by Alexa (owned by Amazon), which tracks usage of computers with the Alexa toolbar. They claim “millions” of users, but their sample is not ascientific one. See ↪link 5.25b.

26 Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Annual Report, Year Ended March 31, 2003, 5.

27 Angela O’Neal, interview, 9 June 2004; Butowsky, interview.

28 Mary Stutz, interview, 11 June 2004.

29 Even anonymously, cookies can be used for more sophisticated tracking of web traffic. See Sane Solutions, Analyzing Web Site Traffic: A Sane Solutions White Paper (North Kingstown, R.I.: Sane Solutions, 2003). Cookies cannot damage your computer or make you vulnerable to hackers. Nonetheless, some web users view them suspiciously and do not allow them on their hard drives. Most reputable sites have privacy policies that state that they will not sell information about you to someone else. But the company could be bought by less privacy-minded owners. Even if you haven’t registered, cookies can gather information on your surfing habits. Advertising companies like DoubleClick place advertisements on hundreds of sites across the Internet and then distribute cookies though each of the ad banners they operate. The reach and breadth of their banners allow their cookies to gather data on web surfers. In effect, you become an unpaid participant in their marketing studies. Pbs.org offers a good model of a privacy policy for a nonprofit organization. See “About This Site, Privacy,” ↪link 5.29a. For more information about cookies and how they work see “Persistent Client State HTTP Cookies,” Netscape.com,↪link 5.29b.

30 Bruce Tognazzini, Tog on Interface (Boston: Addison-Wesley Professional, 1992), 79.

31 Katherine Khalife, “Nine Common Marketing Mistakes Museum Websites Make,” Museum Marketing Tips, 2001, ↪link 5.31; O’Neal, interview.

32Phil Agre, “[RRE] Notes and Recommendations,” email to “Red Rock Eater News Service” rre@lists.gseis.ucla.edu, 8 August 2000, ↪link 5.32.