|

|

|

“Mexican Officials Kick On Women

in Knickers, Do not allow Oklahoma Tourists to Enter Mexico in Plus

Fours” El Universal (“English News Section”),

Mexico City, 14 July 1924.

Read

Story Read

Story  Newspaper Newspaper

This story appeared in the two-page daily English-language

supplement to El Universal, Mexico City’s most authoritative

newspaper at the time. The English-language supplement usually printed

news that El Universal’s editors believed would interest

English-speaking readers who lived in the city more or less permanently,

rather than tourists. Therefore the English-language pages generally

contained business news of interest to local representatives of foreign

firms, a smattering of political news from Britain and the United

States (usually translated from the main part of the paper), social

notes detailing the comings and goings of businessmen, diplomats,

and their families, and extensive coverage of tournaments and dances

at Mexico City’s elite country clubs. The supplement almost

never printed stories about crime, tourism, or the day-to-day workings

of government (neither in Mexico nor abroad.)

So this small story might catch a historian’s

eye because it was unlike the articles around it. As she examined

it, she would ask a series of questions:

A. Why did Mexico City’s most important

newspaper feature two daily pages in English?

The foreign business and diplomatic community

in Mexico City in the 1920s was not large enough to support a newspaper

of its own. Even if every English-speaking household in the city

had subscribed to El Universal, they would not have raised

its circulation figures appreciably. Furthermore, most people living

in Mexico City at the time did not read English. Including the English-language

section could not have brought new readers to the paper, then.

The supplement was expensive to produce, both

because it required hiring journalists, translators, and an editor

fluent in English—as few newspapermen of the time in Mexico

City were—and because the single largest fixed expense for

a newspaper in Mexico at the time was the cost of paper. Adding

even a single sheet daily to El Universal was a big investment.

No other Mexico City newspaper paid for a section in English, but

El Universal stuck with it for four decades. So why would

El Universal’s editors have decided to print a section

of the paper in English every day?

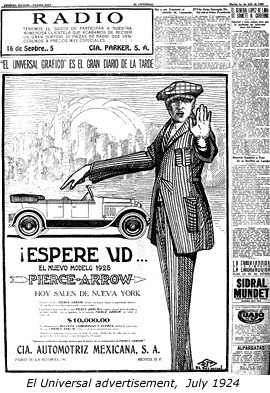

The

advertisements in El Universal provide one possible answer

to this question. They peddled high-end goods—often, imported

items ranging from tennis balls to automobiles. They did not aim to

reach many readers, but focused on a small number of wealthy ones.

This would include Mexico City’s community of English-speaking

resident foreigners, but also included the larger number of relatively

conservative, wealthy Mexicans who would see the inclusion of an English-language

section as a sign of the newspaper’s politics. In the aftermath

of the Mexican Revolution (during which the United States invaded Mexico and

Pancho Villa’s army invaded the United States), this gesture of affiliation

with the United States and its representatives in Mexico suggested

that El Universal did not entirely agree with the new, post-Revolutionary

government’s nationalist policies. This, in turn, would have

hinted at a broader conservatism that wealthier Mexicans, presumably,

would have appreciated. Advertisers in El Universal, therefore,

found the presence of the English-language section a reassuring sign

that they could reach a group of rich, powerful consumers. The

advertisements in El Universal provide one possible answer

to this question. They peddled high-end goods—often, imported

items ranging from tennis balls to automobiles. They did not aim to

reach many readers, but focused on a small number of wealthy ones.

This would include Mexico City’s community of English-speaking

resident foreigners, but also included the larger number of relatively

conservative, wealthy Mexicans who would see the inclusion of an English-language

section as a sign of the newspaper’s politics. In the aftermath

of the Mexican Revolution (during which the United States invaded Mexico and

Pancho Villa’s army invaded the United States), this gesture of affiliation

with the United States and its representatives in Mexico suggested

that El Universal did not entirely agree with the new, post-Revolutionary

government’s nationalist policies. This, in turn, would have

hinted at a broader conservatism that wealthier Mexicans, presumably,

would have appreciated. Advertisers in El Universal, therefore,

found the presence of the English-language section a reassuring sign

that they could reach a group of rich, powerful consumers.

All this, in turn, means that the English-language

section of the paper was not primarily intended as a news source,

but more as a way for the paper to sell itself to readers and advertisers

who would expect to find serious news in the paper’s main

sections in Spanish.

B. Was this story important at the time?

No other Mexico City newspaper covered this story;

nor did it appear in the Spanish-language part of El Universal.

This suggests that newspaper editors thought the story unimportant,

that it appeared in the English-language supplement of El Universal

only as entertaining “filler.” Just because this was

a very minor piece of news in 1924, however, does not mean that

the article lacks value as a historical source in the present day.

Sometimes, placed in their proper context, short newspaper articles

can serve as windows opening onto much larger historical vistas.

The challenge is in deciding what the proper historical context

might be.

C. How was this story related to other articles

printed in the newspaper at roughly the same time?

The story of Mexican officials refusing entry

to a group of women from the United States was not typical of El

Universal’s articles—neither those in the regular

Spanish-language pages nor in the English-language supplement—in

most respects. The paper did not ordinarily cover events at the

border. Even if it did, the crossing between Matamorros and Brownsville

was not an especially busy one and rarely warranted press attention.

It was highly unusual for an article—even a short one—to

report the deeds of consular officials so far from the capital.

Similarly, tourism rarely received media attention in 1920s Mexico.

The article, however, does fit neatly into a

series of stories and images that seemed to fill the paper in the

summer of 1924. There was a sudden rise of attention to women’s

fashion, particularly those fashions that came from abroad and seemed

to make women look masculine. The major issue of the time was the

length of women’s hair, but other aspects of women’s

appearance also caused controversy.

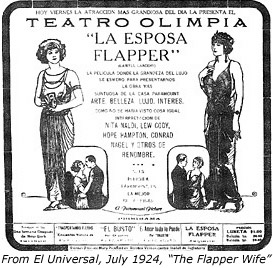

Stories

and images about the trend for masculine-looking women’s attire

sometimes appeared in the news—as when an Italian bishop announced,

in April 1924, that short-haired women would not be offered communion

in the churches of his parish, or in this article about women in “plus-fours”

(short, baggy pants strapped tight just below the knee). More often,

though, changing fashions appeared in newspaper advertisements (the

image of a “modern,” cosmopolitan woman was used to sell

everything from quack medicines to household appliances), in photographs

depicting athletes, celebrities, and high-society functions, and in

reviews of Italian, French, and U.S. silent movies about “flappers.” Stories

and images about the trend for masculine-looking women’s attire

sometimes appeared in the news—as when an Italian bishop announced,

in April 1924, that short-haired women would not be offered communion

in the churches of his parish, or in this article about women in “plus-fours”

(short, baggy pants strapped tight just below the knee). More often,

though, changing fashions appeared in newspaper advertisements (the

image of a “modern,” cosmopolitan woman was used to sell

everything from quack medicines to household appliances), in photographs

depicting athletes, celebrities, and high-society functions, and in

reviews of Italian, French, and U.S. silent movies about “flappers.”

People around the world took an interest in this

new vogue, but in Mexico it seemed especially important because

of the recent Revolution. Women taking up masculine-seeming fashions

symbolized larger change in women’s social roles and the opportunities

available to women, which in turn was part of an even broader upheaval

in social relationships caused by the Mexican Revolution. One of

the reasons that this story from the border would catch a historian’s

eye, then, is that it shows a representative of Mexico’s federal

government opposing—rather than supporting—the new,

“revolutionary” way in which some women were presenting

themselves.

D. What was left out of the story? How can I

find out more?

This newspaper article is so brief that it raises

more questions than it answers. Historians might want to work on

three such questions when analyzing this story. First, what was

going on in Brownsville and Matamorros at the time? Second, who

was that consular official? Third, who were those women from Oklahoma

who wanted to cross into Mexico?

Looking in El Universal from the previous

month begins to answer the first question. President Calles had

visited the region and given a major speech that brought up, among

other things, the issue of women’s roles in reconstructing

Mexico after the Revolution. But once again this raises further

questions. How did people in the area—on both sides of the

border—respond to this speech? Did they even pay attention

to it? What else was going on there? A more complete answer to the

first question would require checking periodicals other than El

Universal, especially newspapers from Brownsville and Matamorros.

Researching the other two questions also requires

moving beyond the pages of El Universal, and eventually beyond

research in periodicals, although it seems likely that local newspapers

would tell more of the story than the newspaper from the faraway

capital of Mexico. To get a sense of the area at the time, tourist

guidebooks and contemporaneous maps are a fine starting point. If

the incident recorded in El Universal’s article became

notorious in the place where it happened, it might have been remembered

by local people in memoirs or oral histories. A visit to the historical

societies and municipal archives of Brownsville and Matamorros would

probably be productive. Documents of the federal government—especially

consular records from both sides of the border—would also

be a good place to search, both to tell more of the story and to

find out a bit more about this particular Mexican Consul in Brownsville.

Finally, to find out more about the women who tried

to get into Mexico while wearing pants will require making a guess

about who they were, based on further evidence from local newspapers

and from consular records. Perhaps they were trying to cross the border

in breeches as a political gesture. If so, they may have represented

an organization of some kind, perhaps a women’s club. The records

of that group would be in an Oklahoma archive. Or, as the conclusion

of the article in El Universal seems to hint, they may have

been prostitutes coming to work at one of the legal brothels (delicately

referred to as “nightclubs”) on the Mexican side of the

border. These bordellos were regularly inspected, and prostitutes

had to carry special licenses. Thus, they too produced many official

documents in which these women might perhaps be found.

This case study shows two aspects of using newspapers

as primary sources—the limits of what can be learned from a

single newspaper story, and the infinite possibilities of looking

at the newspaper as a whole.

The limits on what a single article can tell historians

are clear. In order to understand what the article might mean—or

even to see that it might be interesting in some way—historians

have to begin by knowing something about the newspaper in which the

article appeared. In order to analyze it, they have to look at related

articles in the same newspaper, look at different periodicals, and

then move on to other kinds of documents. For this case study, useful

documents included several kinds of government records, old maps,

and memoirs. Newspapers often give historians a good place to begin

their work, but are very rarely sufficient, on their own, for serious

historical study.

Doing research in newspapers is full of possibilities.

In this case, by taking in a wide range of different periodicals and

by looking not only at the news stories, but also advertisements,

illustrations, movie reviews and other features, historians could

spot a pattern: Mexicans in the mid-1920s seemed to be concerned with

the issue of women who looked masculine. A single article might not

tell a historian very much in itself, but locating many such items

is one of the best ways to spot a broad cultural or social transformation.

In the end, like any primary source for historical

research, newspapers offer us imperfect, but exciting, glimpses of

the past.

|