|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

By about 1920, almost every city and many small towns in the developed world had their own newspapers—at least in places that had a large enough population of people who could read and could afford the small daily expense of buying the paper. Ordinarily, advertisers covered most of the cost of printing and distributing newspapers. Many cities had competing newspapers, some published in the morning, some in the afternoon.

Setting the newspaper in its appropriate technological context is also important. It helps historians sort out what was ordinary about the newspaper for its place and time from what was extraordinary or out of place. To do this, historians make comparisons among several different newspapers from the same date and among issues of the same newspapers. They compare the look of different newspapers from the same time and place—including their typography, illustrations, placement and style of advertisements, number of pages, and page sizes—to get a sense of the economic health and intended audience of the particular newspaper that interests them. They compare the look of different issues of the same newspaper (especially size of headlines and number of photographs or prints) to see if the editors believed that the events covered on the day that interests them were especially important or exciting. Historians also need to have a good sense of what sources the newspaper had for its information and how long the lag time would have been between the events and their appearance in the paper. Reporters’ bylines or bylines from news agencies will help provide a sense of that.

|

||||||||||||

|

finding world history | unpacking evidence | analyzing documents | teaching sources | about |

||

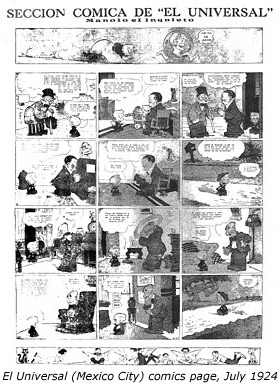

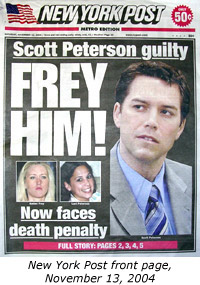

To

attract readers in competitive markets, newspapers publishing in the same

places tried to appear unique. Some aimed for high literary quality while

others tried to catch the reader’s eye with the loudest headlines

and the most lurid graphics. Some tried to print information that appealed

to specific local audiences, such as coverage of high-society parties,

the passenger lists of arriving ocean liners, or especially extensive

classified advertising. Others emphasized features from wire services

including serialized fiction, recipes and other consumer information,

and advice on relationships as well as the more familiar opinion pages,

theater and movie reviews, and comic strips. A good funny page gave newspapers

great appeal and helped build reader loyalty.

To

attract readers in competitive markets, newspapers publishing in the same

places tried to appear unique. Some aimed for high literary quality while

others tried to catch the reader’s eye with the loudest headlines

and the most lurid graphics. Some tried to print information that appealed

to specific local audiences, such as coverage of high-society parties,

the passenger lists of arriving ocean liners, or especially extensive

classified advertising. Others emphasized features from wire services

including serialized fiction, recipes and other consumer information,

and advice on relationships as well as the more familiar opinion pages,

theater and movie reviews, and comic strips. A good funny page gave newspapers

great appeal and helped build reader loyalty.