Getting Started: The Nature of Websites, and What You Will Need to Create Yours

Multimedia

nce you move beyond the text and images associated with most basic history websites into the multimedia found on many exhibition and archive sites, as well as most sites on the history of music and film, you face additional hurdles. Although the web can handle audio and video, it often doesn’t do a very good job compared to dedicated platforms (such as a CD or DVD player), and such multimedia adds a layer of complexity to any website. Two reasons for this complexity exist. First, moving from static elements like text and images to audio and video involves a quantum leap in the heft of a web page, or more accurately the file size of its multimedia components. Second, audio, video, animation, and other multimedia formats unfold over time, and thus raise the question of streaming versus downloading. If a video is 100 megabytes, do you really want to make a viewer wait for the entire file to download before beginning its display—about two hours on a 56K modem or fifteen minutes on a high-speed connection? (In 2004, the number of Americans accessing the Internet with a fast broadband connection finally surpassed the number of slow modem users, but that still leaves tens of millions of potential viewers in a poor position to receive large video files.) The alternative, streaming, downloads only the first bit of the movie and continues to download segments in the background as the viewer begins to watch the film immediately. Impatient viewers clearly prefer this method—yet it means that the website producer has to deal with additional, complicated software on the server.

nce you move beyond the text and images associated with most basic history websites into the multimedia found on many exhibition and archive sites, as well as most sites on the history of music and film, you face additional hurdles. Although the web can handle audio and video, it often doesn’t do a very good job compared to dedicated platforms (such as a CD or DVD player), and such multimedia adds a layer of complexity to any website. Two reasons for this complexity exist. First, moving from static elements like text and images to audio and video involves a quantum leap in the heft of a web page, or more accurately the file size of its multimedia components. Second, audio, video, animation, and other multimedia formats unfold over time, and thus raise the question of streaming versus downloading. If a video is 100 megabytes, do you really want to make a viewer wait for the entire file to download before beginning its display—about two hours on a 56K modem or fifteen minutes on a high-speed connection? (In 2004, the number of Americans accessing the Internet with a fast broadband connection finally surpassed the number of slow modem users, but that still leaves tens of millions of potential viewers in a poor position to receive large video files.) The alternative, streaming, downloads only the first bit of the movie and continues to download segments in the background as the viewer begins to watch the film immediately. Impatient viewers clearly prefer this method—yet it means that the website producer has to deal with additional, complicated software on the server.

Unlike the standards that undergird the web, such as HTML, commercial products that use proprietary technology to structure and serve audio and video dominate streaming media. At the current time, three main formats predominate, each with more or less a third of the market, depending on who you ask: RealMedia from RealNetworks, one of the pioneers in online multimedia during the dot-com boom and still a market leader (though possibly fading); Windows Media from Microsoft; and QuickTime from Apple. RealNetworks, Microsoft, and Apple have each pursued a similar strategy to profit from audio and video, a strategy that luckily benefits consumers but unluckily affects producers of web content: they all distribute free programs for playing audio and video streamed in their format, but charge producers for the means to stream that content. Fortunately the three large companies have also seen the benefit of giving away (or licensing at little cost) restricted versions of their media servers so that small website creators (including virtually all historians) can start to use these products for free. If you do not plan on having more than a few people access your audio or video at one time nor need to display extremely high-quality formats (e.g., full-screen video), these restricted versions will do.11

Each of the three major formats has its advantages and disadvantages, making it difficult to choose one format over the others. To nonaudiophiles, audio sounds roughly the same on all three; more substantial differences occasionally show up in video playback, which is far more taxing on both the server and client computers. (Indeed, though decent audio can be transmitted over a dialup modem, acceptable video requires much higher speeds.) High-volume sites have often chosen the RealNetworks product line because their server software is extremely sophisticated about the way it pushes audio and video out to a variety of users (it can discern how fast each user’s connection is and compensate), and it can handle thousands of streams at the same time. Most viewers and listeners, however, consider RealMedia files to have the lowest (though still acceptable) audio and video quality of the three major formats. Microsoft also has server technology that helps to smooth out playback to large numbers of people and can also handle far more streams than will likely occur on any but the most popular websites. But probably its greatest advantage is Microsoft’s preinstallation of the Windows Media Player on 95 percent of the world’s computers. PC users have to actively seek out the RealMedia and QuickTime players (of course, Mac users have to seek out the Mac version of the Windows Media Player). For this reason alone, Dan Arthurs of StreamingCulture, a site that serves multimedia for numerous arts and humanities organizations, recommends Windows Media for any historian who has to choose a single streaming format. (With a high-capacity server and an audience that includes many artistic Mac users, StreamingCulture streams audio and video in both Windows Media and QuickTime.) If you do choose Windows Media, you need not have a Windows server; the server software runs on other platforms too.12

Apple’s QuickTime (which in turn runs on Windows servers) has traditionally been the choice for websites looking to serve the highest quality video, but its slightly less robust server software (compared to RealMedia and Windows Media) means that it cannot handle huge numbers of visitors as elegantly (again, we are talking about hundreds of simultaneous users or more), and video has been known to be choppier than the other two formats during streaming playback.13 On the other hand, because it uses an open encoding standard, unlike the proprietary “codecs” of RealMedia and Windows Media, the QuickTime format may survive for a longer period of time, and achieve a wider adoption across many devices and platforms, than its rivals. None of the three formats is truly adequate for long-term preservation because they compress multimedia so substantially as to lose considerable information from the original. Arthurs strongly recommends saving both the physical media (if any) on which the audio or video was recorded (e.g., Digital Beta or consumer DV) and a high-quality transfer to your computer (more on this in Chapter 3), in addition to whichever streaming format (or formats) you select.14

Interestingly, the three companies have recently begun to partially support some common and even rival formats. All support the extremely popular MP3 audio standard—a good neutral choice for serving (but not archiving) digitized audio—and some server and player software from RealNetworks supports (perhaps oddly) QuickTime and Windows Media formats. Because most people have more than one of the three main players (and sometimes all three) on their computers, it is difficult to go wrong—inevitably some of your audience will have to download the free player before viewing your content, and you should always include a link to the specific streaming media company’s site for these downloads. Choosing a specific format for your multimedia does entail a commitment, however; switching to another format later on can be difficult.

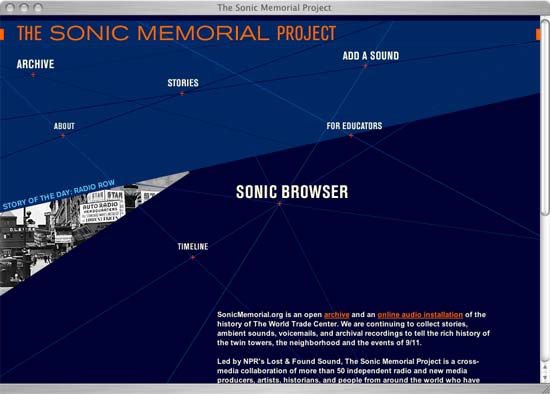

Done well, the addition of audio and video to a site can be affecting. The Sonic Memorial Project, an audio history of the World Trade Center and its collapse on September 11, 2001, has an immediacy that pure transcripts lack. In addition to hearing the voices of hundreds of survivors, visitors can listen to longer segments from the Mohawk iron workers who helped to build the twin towers in the 1970s, and now-lost sounds of people on the observatory deck, in the neighborhood below, and at work in the skyscrapers. The sheer size of its collection of audio files and the creative way that the website allows for visitors to hear audio clips from a wide variety of people in its archive requires (unsurprisingly) a fairly complicated infrastructure, including server software from RealNetworks and extensive programming by Sonic Memorial’s web developer Julian Bleecker.15

Figure 15: The Sonic Memorial Project captures the history of the World Trade Center from its planning and construction to the aftermath of September 11, 2001, through hundreds of audio clips, artfully accessed through a “sonic browser” that masks a fairly complex technical infrastructure.

Few historical projects that require audio will need to reproduce such an effort. Either a “wait until download is complete” system for audio or video files or an installation of the basic (and free) versions of RealMedia, Windows Media, or QuickTime server software will likely suffice for almost all small- to medium-sized sites that are not receiving thousands of daily hits. Regardless, audio or video on the web must be digital rather than analog, which may involve substantial conversion issues, one of the subjects of Chapter 3.

Another popular option for moving beyond static text and images on your website is a commercial product for animation and multimedia called Flash, produced by the Macromedia Corporation, the creators of Dreamweaver. The great technological advantage of Flash versus streaming media software is that it permits files that are small relative to video files (but still not tiny, particularly for those viewing the web through a slow modem connection) to seem like highly advanced graphical experiences. Moreover, Flash allows for interactivity with this content. To do its magic, however, Flash requires special software that plugs into your web browser and that takes over the display when it encounters a Flash file; luckily most computers now come with Flash preinstalled. More significant disadvantages of Flash include its poor accessibility to those with visual disabilities (see Chapter 4) and the difficulty search engines like Google have had finding information within sites heavily reliant on the technology—making it harder for your potential audience to find your online project. Also, like streaming media, Flash’s costs are borne by the producers rather than the users. Creators of Flash content must buy special production software from Macromedia, and they also must spend the time to learn how to create Flash files, which differ substantially from the files created with an image editing program like Photoshop.16

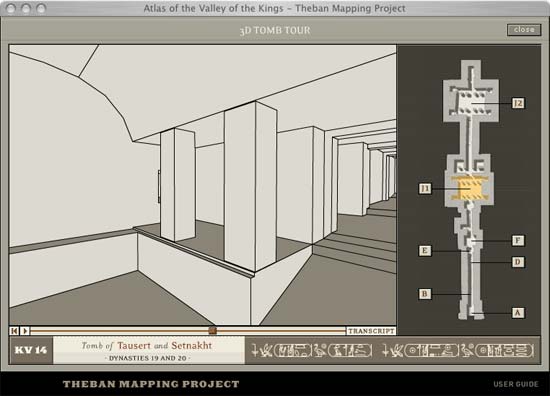

Many of the best historical sites that use Flash combine its potential for interactivity with compelling graphics that help the viewer understand an event or place that would be difficult to describe with mere words. For example, National Geographic’s Remembering Pearl Harbor places its archival photographs, video footage, and first-hand narratives into a timeline and map that the user can click on to go directly to key moments, such as the first sighting of an aircraft off Oahu. Using Flash technology, the user can then zoom into the map and choose related historical documents to study further. Just as impressive as Remembering Pearl Harbor in its use of Flash to convey visually the complexity of the past is the Theban Mapping Project, which provides interactive, highly detailed birds-eye maps of the Theban Necropolis and especially the Valley of the Kings, the location of so much important Egyptian archaeology. A 3-D re-creation of one Pharaoh’s tomb, over 250 zoomable and pannable maps, and links from these interactive maps to over 2,000 images, provide a rich historical panorama of the era of the Rameses and their complex funerary constructions that easily rivals any book on the subject.17

Figure 16: The extensive archaeological resources of the Theban Mapping Project include 3-D renderings of the tombs of Ecyptian pharaohs, accomplished through the use of Macromedia’s Flash technology.

11 Market share from one 2004 report shows Microsoft and Apple essentially tied for first place, followed by RealNetworks: Microsoft Media Player, 38.2%; Apple QuickTime, 36.8%; RealNetworks Real Player, 24.9%. Michael Singer, “Apple Readies Next-Gen MPEG-4 Part 10,” InternetNews, 11 June 2004, ↪link 2.11a; RealNetworks, ↪link 2.11b; “Windows Media,” ↪link 2.11c; “QuickTime,” Apple, ↪link 2.11d. Several open source multimedia formats, such as Ogg Vorbis (↪link 2.11e) for audio, are free for both producers and end users, but very few people have downloaded the necessary programs to create, listen to, or watch these marginal formats.

12 Dan Arthurs, email to Dan Cohen, 20 August 2004.

13 “The Faws: What Streaming Video/Audio Formats Are Available?” filmmaking.net, ↪link 2.13a; “Designing Web Audio: Chapter 5: Introduction to Streaming Media,” O’Reilly Online Catalog, ↪link 2.13b; “Tips and Tricks: Streaming Media Options for the World Wide Web,” Catalyst, ↪link 2.13c.

14 Arthurs, email; Mary Ide, Dave MacCarn, Thom Shepard, and Leah Weisse, “Understanding the Preservation Challenge of Digital Television,” in Building a National Strategy for Preservation: Issues in Digital Media Archiving (Washington, D.C.: Council on Library and Information Resources and the Library of Congress, 2002), 67–79, ↪link 2.14a; Howard D. Wactlar and Michael G. Christel, “Digital Video Archives: Managing Through Metadata,” in Building a National Strategy for Preservation, 80–95, ↪link 2.14b.

15 The Sonic Memorial Project, ↪link 2.15.

16 “Macromedia Flash MX,” Macromedia, ↪link 2.16a. Macromedia has recently tried to improve the accessibility of Flash. See “Accessibility and Macromedia Flash MX 2004,” ↪link 2.16b, and Bob Regan’s blog on accessibility for Macromedia products, ↪link 2.16c.

17 “Remembering Pearl Harbor,” National Geographic, ↪link 2.17a; Theban Mapping Project, ↪link 2.17b.